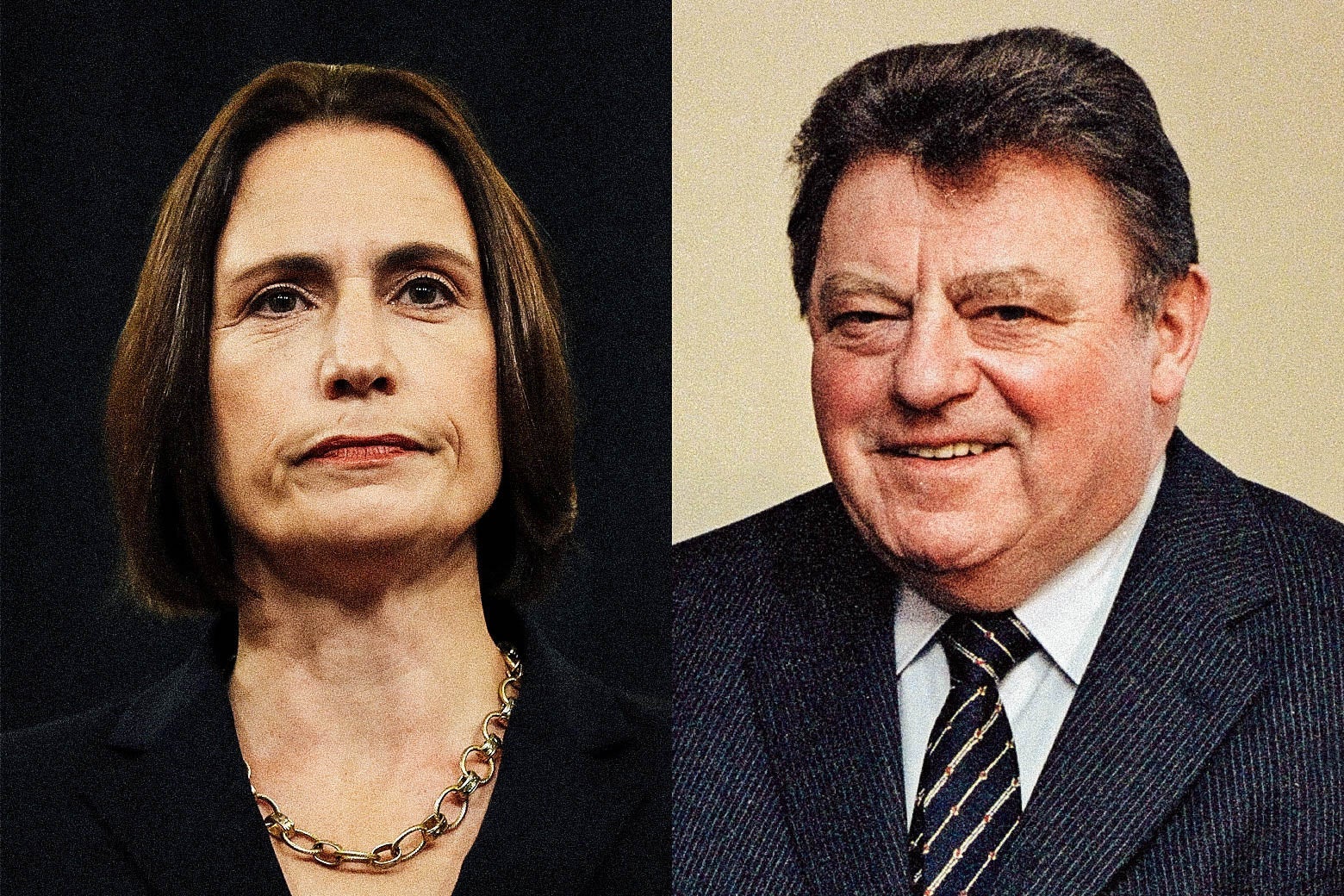

How do you know that the Russians are going to mess with our elections again next year? Because they’re already hard at work at it—in full view of the U.S. electorate. On Thursday morning, Fiona Hill, the former senior director for European and Russian affairs on the National Security Council, testified as part of the House Intelligence Committee’s impeachment hearings. In her initial statement, she urged committee members not to “promote political driven falsehoods,” particularly the “fictional narrative” that it was, in fact, Ukraine that meddled in the 2016 elections, not Russia. According to this version of events, the Democratic National Committee hired the security company CrowdStrike to fabricate a report that would blame Russian hackers for accessing and then sharing Democrats’ emails with WikiLeaks. The purpose of the whole operation was to create the foundation for the Mueller probe and frame President Trump as a Russian operative. The Ukrainian connection? The conspiracy theory says that CrowdStrike is owned by a wealthy Ukrainian. Except it isn’t.

As Hill explained, this false narrative “has been perpetrated and propagated by the Russian security services themselves.” Her claim is supported by how astoundingly similar this current situation is to previous scandals influenced by Russian disinformation tactics, stretching back many decades. They follow a very simple pattern: First, a connection is established between Russian operatives and influential figures in a targeted, usually Western, country. Second, those figures are approached by seemingly credible people who offer them limited and tentative information that, if true, would be helpful to their mission. Third, the influential figures publicize and amplify the information through their usual communication channels. Fourth, though no actionable or solid evidence has been provided, a scandal erupts, often taking down elected officials.

This is what happened in 1962, when then–West German Minister of Defense Franz Josef Strauss was forced to step down. In October of that year, against the backdrop of the Cuban missile crisis, the German news magazine Der Spiegel had published documentation showing that West German armed forces were not sufficiently prepared to withstand an attack from the Soviet Union while waiting for the U.S. and other NATO countries to respond with military aid. Strauss claimed that the documentation published by Der Spiegel was classified and had Rudolf Augstein, the magazine’s editor in chief, arrested. But postwar West Germany held freedom of the press in high regard, and Strauss’ actions were seen as direct retaliation to Augstein, with whom he had a long-running and very public feud. Prior to the publication of the purportedly classified documents, Der Spiegel had made a number of corruption allegations against Strauss, accusing him of taking kickbacks from, among others, West German construction giant FIBAG and Lockheed, for awarding the companies lucrative defense contracts. Facing criticism for impeding freedom of the press and silencing inquiries into his alleged corruption by having Augstein arrested, Strauss was forced out of office in December 1962.

What is rarely talked about anymore, however, is where Der Spiegel got the information that would initially set their investigations of Strauss in motion. As one of the sources close to the affair on the KGB side, Ilya Dzhirkvelov wrote in his 1987 book that Soviet leaders considered Strauss one of “the most dangerous people in West Germany.” Dzhirkvelov describes how West German journalists on a PR trip to Moscow in May 1961 were told that the KGB possessed highly classified kompromat, or compromising material, on Strauss. (Der Spiegel denied this at the time, but several sources have since supported Dzhirkvelov’s version of events.) The leads the KGB provided the West German journalists weren’t true. But they eventually produced so much smoke that nobody doubted that there was a fire somewhere, too. Even though the original information wasn’t accurate, the KGB’s effort still had the intended effect by prompting reporters to start digging and eventually find something real.

Compare this to what happened during the U.S. presidential election in 2016, when WikiLeaks (the influential figure) received a cache of emails stolen from the Democratic National Committee (the Western target) through a so-called spear-phishing attack (by Russian operatives). Both the GOP and several news outlets had a field day with the leaked emails. But initially, the biggest scandal to erupt from the hack was the accusation that members of the DNC leadership had conspired against Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders during the 2016 primaries. Like in the Strauss case, no definitive smoking gun was ever found. The evidence primarily consisted of discussions about actions that may or may not have been carried out. And yet, the pressure was still high enough that several members of the DNC leadership resigned, including Chair Debbie Wasserman-Schultz.

Another example, involving a somewhat less high-ranking public official, is what happened to the American diplomat Brendan Kyle Hatcher. He was sent to the U.S. Embassy in Moscow in 2008 on a mission to promote human rights and freedom of religion, which included leading the compilation of the State Department’s Freedom of Religion report. This work involved talking to religious groups “outside the mainstream,” which often faced both official and unofficial discrimination, as CNN reported at the time. In 2009, the FSB (the KGB’s successor under the Russian Federation) posted a poorly doctored video online—which pretty much everyone could tell was a fake—supposedly showing Hatcher having sex with a prostitute. Still, it became enough of a PR stink for the U.S. that the State Department had to issue defensive statements on Hatcher’s behalf. He was gone by 2010. (It’s unclear whether it was his decision.) As of September 2019, he works in a much less public position at the U.S. Embassy in Montenegro.

The main difference between the 1962 operation and the ones in 2009 and 2016 is the emergence of the internet and social media. Western journalists no longer have to go to Moscow to receive compromising leads: Now, evidentiary material in the form of written conversations can be snatched from email servers and sent to those who hold big, online megaphones without anyone ever leaving their desks. And more importantly, the great amplifier that is the social media ecosystem can ramp up a scandal and outrage in a matter of days, which is exactly what happened to the DNC in 2016. The Strauss scandal almost took two years to result in a public resignation.

This time, Republican members of the House Intelligence Committee are holding the megaphone. The sequence of events is repeating once again. The question is whether it will lead to any resignations this time, or whether the testimony of witnesses like Hill can stop this branch of the Russian disinformation campaign in its tracks.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.