Foreward

"…the most powerful and aesthetically pleasing of the church structures"

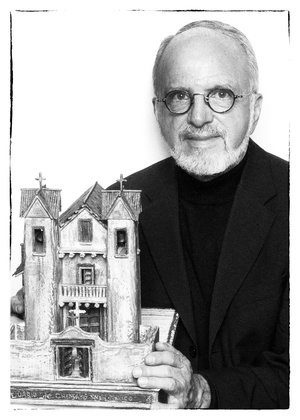

Miniatures have been part of cultures around the world for thousands of years. The role that small things play in society is significant, diverse and reflects cultural values. It includes toys for play, objects for religious ceremony, models for architecture and products, and works of art. The Mini Time Machine Museum of Miniatures in Tucson, Arizona is dedicated to preserving and advancing the art of miniatures and exhibits a wide range of small-scale objects. In the fall of 2016, the museum will present Churches of the Southwest: Wood Sculptures by Roberto (Bob) Cardinale. This exhibition is a homecoming of sorts for Bob who was a Professor of Art at the University of Arizona in Tucson from 1974-1981. Having lived in Tucson, Bob is familiar with two significant Southwest mission churches located south of the city, Mission San Xavier del Bac and Mission San Jose de Tumacácori. He decided to sculpt these two churches and the San Xavier del Bac Funeral Chapel for the Tucson exhibition. Just prior to creating the Tucson missions, Bob completed a series of seven Texas mission churches, so it seemed timely to publish a revised edition of Churches that would include the eleven new pieces and coincide with the presentation at The Mini Time Machine Museum.

Cardinale’s miniature churches are not exact replicas of their real-world counterparts; instead, his small-scale sculptures capture the age, spirit and beauty of these historic landmarks. Cardinale carves the churches from roughhewn pine and attentively finishes the surfaces with paraffin, paint, graphite and gold leaf to capture the spiritual essence of each church. The resulting sculptures demonstrate the passage of time, tell of the desire for respite from the struggles of everyday life, and glorify the artistic accomplishments of bygone generations.

Many churches house shrines representing their patron saint, to which pilgrims pay homage. In the Southwest, it is common to leave Milagros (folk charms used as votive offerings for healing), or other personal items on a church altar that has been designated for the saint. Alluding to this practice, Cardinale sometimes includes drawers in the bases of his sculptures. The drawers contain small assemblages created by his wife, PJ Cardinale, reminiscent of these ceremonial items. The inclusion of these compartments holding devotional objects also brings to mind reliquary boxes of the medieval period. Often designed in the shape of a church, reliquary boxes were purported to contain the bones or personal items of a saint. These chasses, as they were also called, were generally housed in cathedrals. Pilgrims would travel long distances to be in the presence of the saint’s bones, believing that the saints would intercede on their behalf and aid in healing.

It is interesting that Cardinale portrays churches on a miniature scale, especially because real-world churches are majestic buildings. Massive scale, soaring towers, vaulted ceilings and lavish decoration invited congregations to look toward the heavens and note that their lives were at the mercy of the all-seeing divine who gazed down upon the world and determined their fate. By miniaturizing a church as Cardinale does, the viewer gains an overarching view of the church, a godlike perspective that is not possible in the real world. This new perspective affords the opportunity to contemplate the church in a broader context and reflect on the role religion and spirituality have played in human history. Cardinale’s work is a beautiful example of contemporary miniature art representing cultural values and documenting history while delighting the senses.

-Lisa Hastreiter-Lamb, Executive Director, The Mini Time Machine Museum of Miniatures, Tucson, AZ

"he humanizes these structures with such sensitivity, one percieves in his pieces that man is as central to the Divine, as the Divine is to man."

Roberto Cardinale's Narrative

The great cathedrals of Europe and the Americas date to a time when the Church dominated village life. Vaulted ceilings, ornate floors flooded with the light from stained glass windows and spaces filled with the play of incense and sound, imparting an experience of transcendence and communion with the Divine. The mystical beauty of these spaces no doubt contrasted dramatically with the physical lives of those who prayed there. Even the humble interiors of our New Mexican churches, built from mud and wood, thousands of miles from their cathedral cousins, also succeeded in this apiration, perhaps all the more so for their humility and bond with the earth.

Santa Fe artist Roberto Cardinale grew up in an Italian Catholic family. Leaving college after nearly completing a degree in engineering, he entered a monastery to pursue a life of religious devotion. As a Benedictine monk, he inhabited a world of tradition and ritual, informed by the design of its sacred spaces. He studied ecclesiastical architecture there and knows well what he terms, “…the nature of church, the idea of spiritual and intellectual beliefs reflected by the structure itself, lifting and soaring to the heavens.” After five years, he left the monastery to study art, though his love for its structures and sacred ideas persisted. Today, he builds churches.

Cardinale’s sculptures are interpretations of church edifices. He strives to capture the emotion and history that is imbued in the architecture itself. Some are well-known European cathedrals, like Chartres, in France, but among his favorite subjects are the village churches of New Mexico, like the Santuario de Chimayo. He constructs his sculptures from pine and includes details like pin-hinged doors, window frames and crosses, as well as incorporating 22K gold leaf. Some sculptures have secret drawers in the bases, which incorporate assemblages done by his artist-wife, PJ Cardinale, who he met in art school after leaving the monastery. These narratives use found objects and images that relate to the people who might well have been those who worshiped in the very churches that inspired these sculptures. The finished pieces vary in scale, from 8” x 8” to 12” x 16” and are as high as 18"-20” or more.

The surfaces of his pieces are cut and carved from rough sawn pine, never quite flat, but made up of multiple facets. He stains the entire piece, rubs all the surfaces and details with paraffin, paints them with 3-4 colors or more, then scrapes with a blade and paints again until multiple layers are applied. The final scraping reveals shades of color, which he finishes with a graphite rubbing. This deepens the tones and gives the works an aged appearance suggesting the history and wear the structure has endured. The resulting surfaces suggest the paintings of Richard Diebenkorn, an artist who has greatly influenced Cardinale’s work.

There is something quintessentially “Santa Fe” in Cardinale’s story and more to his life than his occupation in the monastery. He holds a doctorate in Art Education, is a former president of Museum of New Mexico foundation and came to Santa Fe from the San Antonio Art Institute in Texas where he was president and before that, a Director of the Program in Artisanry and faculty member at Boston University. All along he desired to create his own work and claim his identity as an artist and seeker.

Through Cardinale’s treatment, even the grand and formal Medieval cathedral of Chartres, is imbued with humility. Perhaps more than glory in God, we see in his works the glory of the people who built, prayed and celebrated within them. No doubt he is concerned with questions of faith and spirit, and man’s place within the sacred order. Because he humanizes these structures with such sensitivity, one percieves in his pieces that man is as central to the Divine, as the Divine is to man.