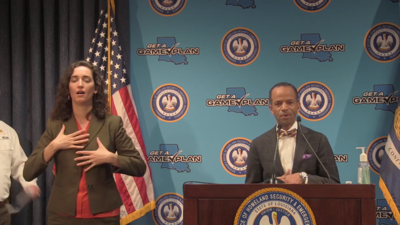

(The Center Square) – Louisiana is launching a task force in hopes of tackling health disparities related to the COVID-19 pandemic, Gov. John Bel Edwards said Friday.

Though the state’s population is only about 32 percent black, about 70 percent of the state residents who have died from COVID-19 have been black. Similar disparities have been observed nationwide.

The Louisiana COVID-19 Task Force will include academics, health care providers and public health officials. The immediate goals are to make sure all communities have accurate and timely information about COVID-19 safety and prevention, disseminate best practices for treating COVID-19 patients with underlying health problems, and promote access to testing, Edwards said.

Edwards stressed the group’s work will benefit the entire state, not just majority-minority communities.

“We want to make sure that we have better health outcomes on the other side of this pandemic as well,” Edwards said.

The vast majority COVID-19 tests in Louisiana are being performed by commercial clinics that don’t report the patient’s race, so state officials are unable to compare the rate of testing and infections to the death rate, Edwards said, pointing to another area of potential study.

Earlier this week, Dr. Corey Hebert, a New Orleans-based pediatrician associated with LSU and Dillard University, joined Edwards’ daily COVID-19 press briefing to talk about the disparity in health outcomes for black residents, which have been apparent since long before the current pandemic arrived.

“African Americans are the most vulnerable by being disenfranchised and systematically marginalized for generations,” Hebert said. “This disease will shine a very bright light on a weakness in our society.”

While black workers being over-represented in the service industry may play a role in that vulnerability, Hebert said, the “social determinants of health” as defined by the federal Centers for Disease Control likely are far more important. Conditions in the places where people live, learn, work, and play, such as safety, education and access to healthy food, affect a wide range of health risks and outcomes, the CDC says.

In the short term, personal changes like eating better, exercising more and trying to reduce stress will be important, Hebert said. But research shows black people tend to have worse health outcomes than white people even when taking into account income, neighborhoods, chronic health conditions and insurance coverage, he said.

Asked about racial differences in the COVID-19 death rates during a recent online forum, U.S. Sen. Bill Cassidy, a Louisiana Republican and medical doctor, pointed to high rates among black people of diabetes, hypertension and obesity, all of which are thought to make death from the illness caused by the new coronavirus more likely.

“If you control for obesity, diabetes and high blood pressure, the racial differences would not be as great,” Cassidy said. “This is not to minimize racial disparity, but this is to seek a scientific understanding of it.”

In a letter to Gov. Edwards that he shared publicly, state Rep. Royce Duplessis, a New Orleans Democrat, said black people being more likely to rely on public transit might be another factor affecting their vulnerability to COVID-19, which spreads through close human contact. Some studies have shown minorities are less likely to have jobs that allow working from home.

Duplessis said any analysis of COVID-19 disparities should factor in policies related to housing, environment, transportation and access to health care and healthy food.

“I believe this is not simply a conversation around health disparities alone,” his letter reads in part. “This is a broader conversation about socio-economic policies that have institutionalized these poor health outcomes.”