A Biblical Mystery at Oxford

A renowned scholar claimed that he discovered a first-century gospel fragment. Now he’s facing allegations of antiquities theft, cover-up, and fraud.

On the evening of February 1, 2012, more than 1,000 people crowded into an auditorium at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The event was a showdown between two scholars over an explosive question in biblical studies: Is the original text of the New Testament lost, or do today’s Bibles contain the actual words—the “autographs”—of Jesus’s earliest chroniclers?

On one side was Bart Ehrman, a UNC professor and atheist whose best-selling books argue that the oldest copies of Christian scripture are so inconsistent and incomplete—and so few in number—that the original words are beyond recovery. On the other was Daniel Wallace, a conservative scholar at Dallas Theological Seminary who believes that careful textual analysis can surface the New Testament’s divinely inspired first draft.

They had debated twice before, but this time Wallace had a secret weapon: At the end of his opening statement, he announced that verses of the Gospel of Mark had just been discovered on a piece of papyrus from the first century.

As news went in the field of biblical studies, this was a bombshell. The papyrus would be the only known Christian manuscript from the century in which Jesus is said to have lived. Its verses, moreover, closely matched those in modern Bibles—evidence of the New Testament’s reliability and a rebuke to liberal scholars who saw the good book not as God-given but as the messy work of generations of human hands, prone to invention and revision, mischief and mistake.

Wallace declined to name the expert who’d dated the papyrus to the first century—“I’ve been sworn to secrecy”—but assured the audience that his “reputation is unimpeachable. Many consider him to be the best papyrologist on the planet.” The fragment, Wallace added, would appear in an academic book the next year.

Though he didn’t mention it onstage, Wallace had recently joined something called the Green Scholars Initiative. The program was funded by the Green family, the evangelical billionaires who own the Hobby Lobby craft-store chain. It gave handpicked scholars access to the thousands of artifacts the family had collected for their Museum of the Bible, a soaring $500 million showplace that would open a few years later near the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Wallace’s ties to the Greens made it easy for observers to connect the dots: The Mark papyrus had to be one of the manuscripts the Greens had bought for their museum. And the papyrologist who worked out its first-century date had to be the world-renowned classicist Dirk Obbink. The Greens were known to have hired him as a consultant during their antiquities buying spree.

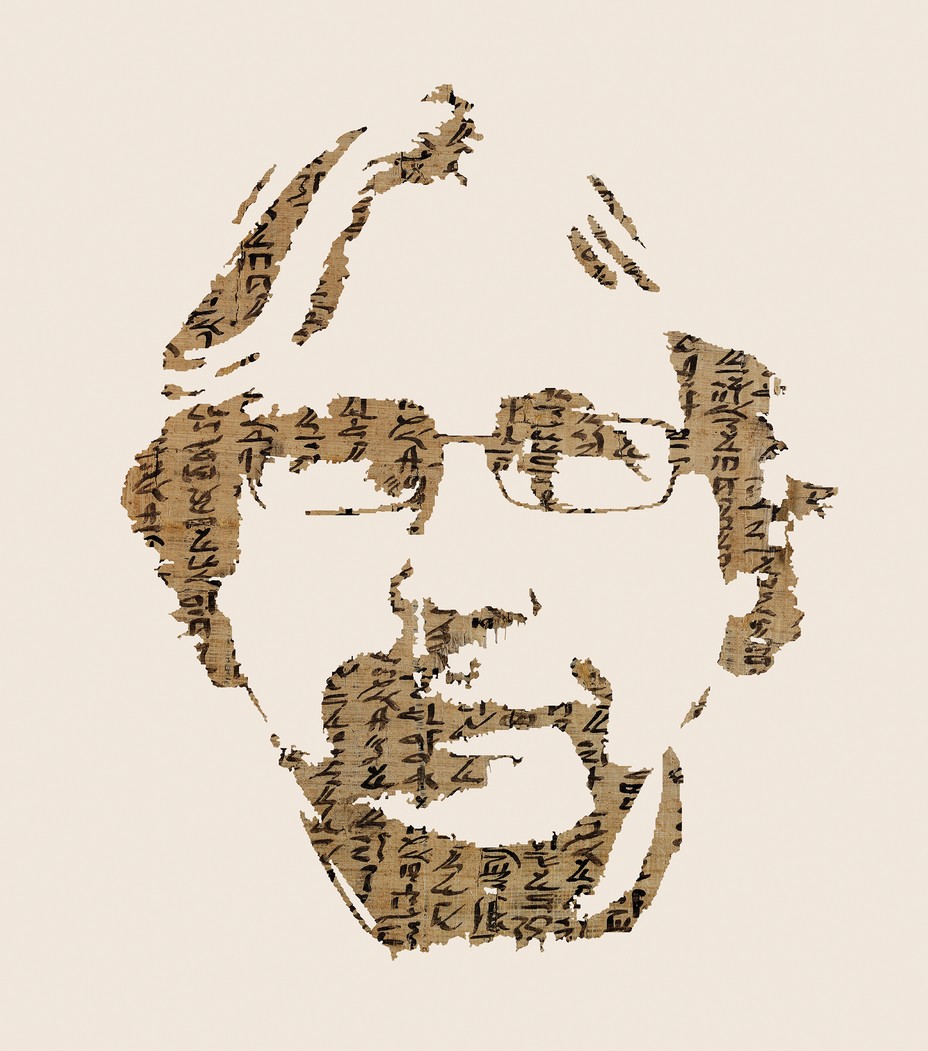

His enlistment had been a coup. A tall Nebraskan with a mop of sandy hair, Obbink was in his mid-40s in 2001 when the MacArthur Foundation awarded him a half-million-dollar genius grant. His technique for reassembling papyrus scrolls carbonized by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in a.d. 79 was a feat of three-dimensional puzzle solving.

Sought by universities and cultural institutions the world over, Obbink taught at Columbia before leaving, in 1995, for Oxford, home to the world’s largest collection of manuscripts from the ancient world: half a million papyri that a pair of young Oxford scholars had excavated in Egypt a century earlier. Obbink’s post as a general editor of the collection—the media sometimes called him its “director,” though officially no such title exists—made him one of his field’s most powerful figures. Wallace had not overstated his qualifications.

But years passed with no news of this “first-century Mark,” as the phantom manuscript came to be called. There was no book in 2013, no exhibit when the museum opened in 2017. Wallace’s blog filled with hundreds of comments. “It has been 5 years,” readers complained. “Hurry up!” One man simply quoted from the Book of Proverbs: “Expectation postponed makes the heart sick.”

Yet in 2018, when Obbink finally published the fragment, it made certain hearts even sicker. The Greens would see their dreams of a first-century gospel dashed. The University of Oxford would be thrust into the news in a labyrinthine case of alleged antiquities theft, cover-up, and fraud. And one of the most illustrious figures in classics, though protesting his innocence, would find himself at the center of a trans-Atlantic investigation.

Dirk Obbink had rummaged for diamonds in the rough since his boyhood in Lincoln, Nebraska. In 2002, the year after he was awarded the MacArthur prize, his mother, Dorithy, told Smithsonian magazine that as a child her son had haunted thrift shops and the town dump, coming home with “a bunch of junk.” His fascination with other people’s trash carried into his years in New York, where he took his daughter dumpster diving.

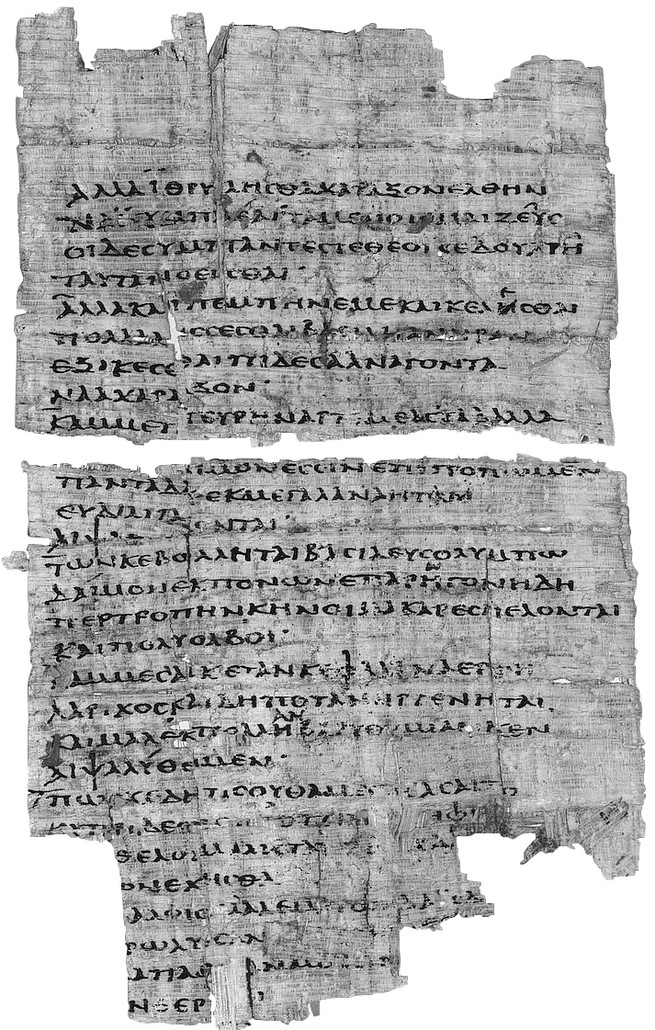

That papyrology called to him was perhaps little wonder. Papyrus was the ancient world’s paper, a disposable medium made of reeds harvested along the Nile. Its 1,000-year heyday as a writing surface coincided with the Greco-Roman era, the fall of the pharaohs, the birth of Christianity, and the advent of Islam. Obbink taught students how to mine the brownish, jigsaw-puzzle-like fragments for lost works of Greek literature and philosophy.

No collection came close to rivaling the one Obbink helped oversee at Oxford’s Sackler Library. The Oxyrhynchus Papyri, named after the lost Egyptian city from whose ancient rubbish heaps they were excavated, contained forgotten works of Sophocles, Menander, and Sappho; love spells and horoscopes; early gospels and Greek translations of the Hebrew Bible. Deciphering the texts is so laborious—and oversight so strict—that just 1 percent of the fragments have been published since their discovery. As a decoder of crumbling, half-vanished manuscripts, Obbink was “an absolute master,” his friend David Sider, an NYU classicist, told me.

When he gave students his attention, they found him mesmerizing. But Obbink was often as inscrutable as the texts he placed under his microscope. Despite boyish looks—an open face beneath a helmet of center-parted bangs—Obbink had a wooden air and monotone voice that struck some people as “cold” or, as one former student put it, “whatever the opposite of charisma is.” He was “never quite there,” another pupil said.

Sider learned not to ask personal questions. “He’d start to be vague,” Sider told me, or “his eyes would start to look elsewhere.” Friends tell a story from Obbink’s graduate-school days at Stanford, when his then-wife returned to their small apartment to find a grand piano monopolizing the living room. “She said to him, ‘Oh, I didn’t know you played,’ ” a former colleague recalled. “He said, ‘Well, you never asked.’ ”

There were surprises at work, too. In 2003, after eight years at Oxford, Obbink was hired by the University of Michigan for a tenured, full-time chair in papyrology at a salary of $105,000. Though he was eminently qualified, the offer was largely an effort to keep his new wife, an esteemed faculty member, at the school. The couple had a young child, and administrators were sympathetic to the strain a long-distance marriage would put on the family.

A few years later, a Michigan classicist named Ruth Scodel was perusing Oxford’s course offerings when she came across a Greek-poetry class. Its teacher was a man she thought worked down the hall from her in Ann Arbor. “I went, What?! ” Scodel recalled.

The revelation that he’d never stopped teaching at Oxford—despite the lengths to which Michigan had gone to help his family—eroded his decades-long friendship with Richard Janko, who’d chaired Michigan’s classics department when Obbink was hired. “It shook my confidence in his character,” Janko told me. (Obbink’s lawyer says that both Oxford and Michigan “were aware and had given unequivocal contractual permission” for Obbink to hold a dual appointment.)

On April 10, 2012, three weeks before he parted ways with the University of Michigan, Obbink visited the county clerk in Ann Arbor. He filed paperwork for a new business, listing its principal address as Room 2151 at 435 South State Street—his soon-to-be-former office in the Michigan classics department. The company’s name, he wrote, was Oxford Ancient.

Founded by King Henry VIII in 1546, Christ Church is the most picturesque of the colleges that make up the University of Oxford. The poet W. H. Auden, the philosopher John Locke, and several British prime ministers were educated on its castlelike grounds, parts of which stand in for Hogwarts in the Harry Potter films.

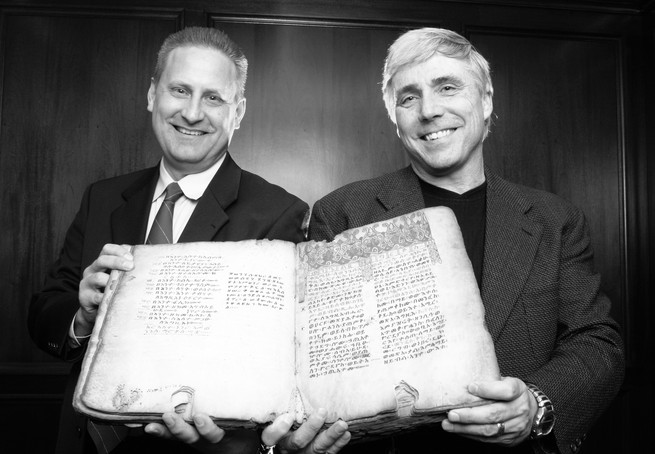

One night in November 2011, two American evangelicals walked up a flight of stairs in a Gothic bell tower on Christ Church’s central quad. Scott Carroll and Jerry Pattengale had been friends since their days together in a different Oxford—the city in southwest Ohio, where they each earned a doctorate in ancient history, at Miami University. Both had taught at Christian colleges and advised well-to-do collectors before Steve Green, the president of Hobby Lobby, hired them to lay the intellectual foundations for a national Bible museum.

Carroll was put in charge of acquisitions, a post that played to his self-image as an impresario called by God to summon texts from the farthest reaches of the globe. His cellphone’s ringtone was the theme from Indiana Jones. A promotional photo, captioned great scott!, depicts him in shorts and a fedora, swinging through the jungle on a rope.

The more sober-tempered Pattengale was named executive director of education; his job was to establish the Green Scholars Initiative, recruiting world-class academics to mentor the students the Greens would invite to research their fast-growing collection.

At the top of the stairs that evening, Dirk Obbink opened a black door and let the two men into his office, a suite of rooms with a kitchen, a bathroom, and a pair of mummy masks that gazed at visitors from across a pool table. By then he’d been on the Hobby Lobby payroll for about a year. For Carroll, he vetted manuscripts that dealers across the world were clamoring to sell to the Greens. For Pattengale, he would teach papyrology to Green Scholars at summer seminars.

They spent an hour discussing Obbink’s latest work. Then, as Carroll and Pattengale stood to leave, Obbink called to them, as if stopped by a stray thought. “Well, wait a minute,” he said. “I have something here you might be interested in.” He padded behind the pool table and opened a manila folder.

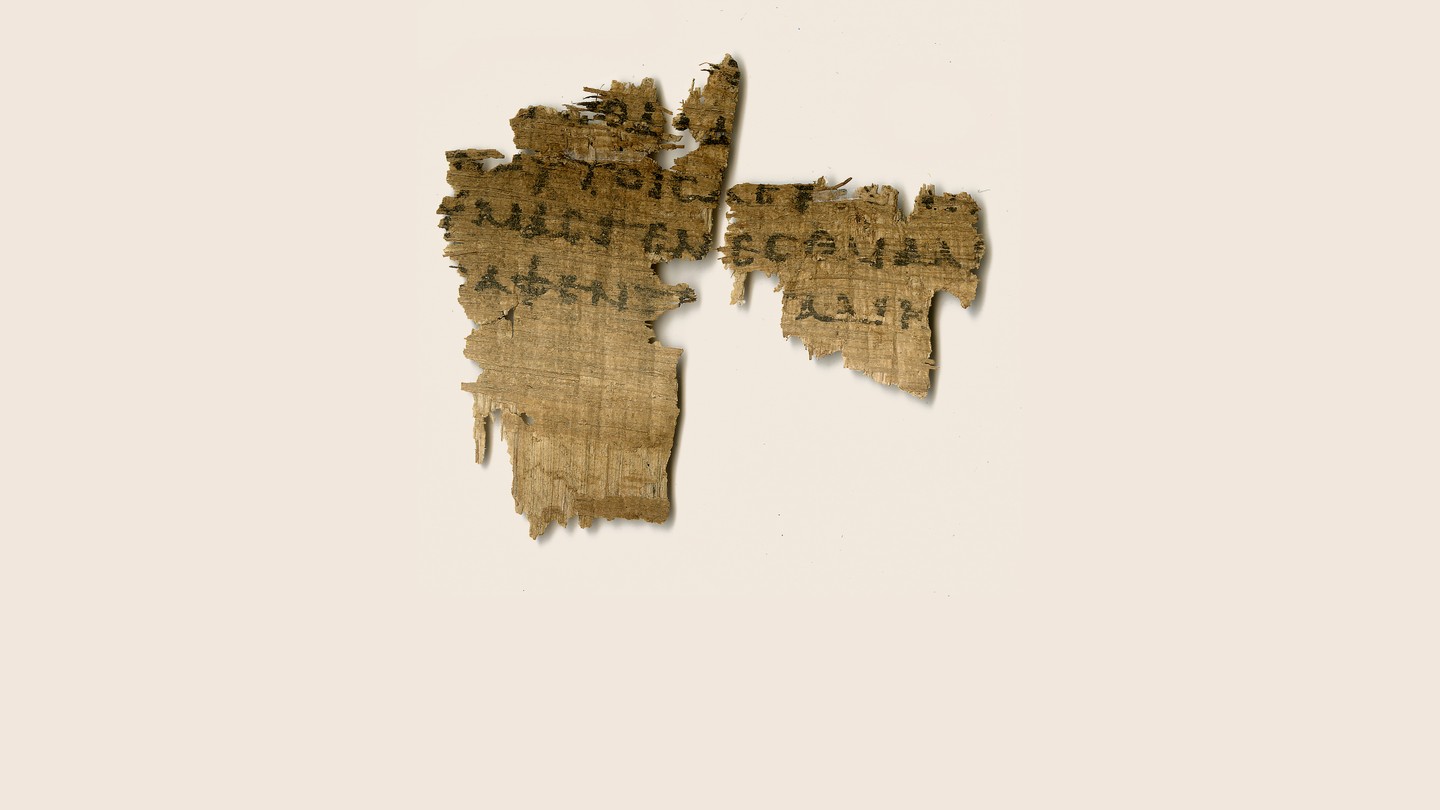

Inside, in plastic sleeves, were ancient pieces from each of the four New Testament Gospels. Obbink tweezed out a fragment of Mark—a small, hatchet-shaped papyrus with verses from the gospel’s first chapter—for his visitors to see. The shape and strokes of certain letters, he explained, were hallmarks of first-century handwriting. Obbink described the fragment as part of a “family collection” and, according to Carroll, “offered it for consideration” for Hobby Lobby to buy.

Pattengale felt momentarily paralyzed, while Carroll paced the room, delirious. Everything they’d worked on up to that point seemed to suddenly pale.

When Pattengale flew home to Indiana the next day, “I told my wife, Cindy, ‘If this proves to be first-century, I may be involved in researching one of the most important pieces of the Bible ever discovered.’ ”

Steve Green had loosed tidal forces when he entered the antiquities market in 2009. He was a motivated, first-time buyer with millions to burn in the midst of a global recession. Strangers bearing ancient scrolls, oil lamps, and incunabula approached museum officials unbidden at restaurants, college lecture halls, even supermarkets.

One would-be seller claimed to have a 5,000-year-old Bible that had been perfectly preserved in ice atop Mount Ararat. Another brought a box of manuscripts to the parking lot of a Cattlemen’s Steakhouse near Hobby Lobby headquarters, in Oklahoma City. When Carroll rebuffed him, the dealer set the box on the trunk of Carroll’s car, then dashed off, yelling, “You’ll love these. Call me!”

In five years, Green acquired more than 40,000 artifacts, from cuneiform tablets and Dead Sea Scrolls to Jewish Torahs and early-American Bibles. But he wasn’t indiscriminate. “We’re buyers of items to tell the story,” Green once said. And the story of Christianity he wanted to tell was of the Bible as a God-given record of “absolute authority and reliability.”

The Greens didn’t want another Creation Museum or Noah’s Ark theme park. They envisioned a “Christian Smithsonian,” as the scholars Candida Moss and Joel Baden described it in their book Bible Nation—an elegantly designed, intellectually serious institution that chronicled the Bible as a profoundly influential historical manuscript.

But secular scholars had doubts. Even before it opened its doors, some critics regarded the Museum of the Bible as little more than a dressed-up version of the many evangelical causes the Greens poured their wealth into—a ministry, in all but name, that cast the New Testament as the unfiltered word of God and America as a Protestant nation. Its detractors saw the Greens as too invested in a particular set of religious beliefs to present the Bible’s many texts and traditions dispassionately.

Obbink was part of the museum’s answer to such criticisms. He was so towering a scholar that the Greens could counter accusations of religious bias simply by citing his involvement. He was, in Carroll’s words, “a person that has no agenda whatsoever.” When it came to papyrus—the predominant writing surface at the dawn of Christianity—the Greens could point to Obbink as an impartial arbiter, someone who could tell the honest brokers from the hucksters, the great finds from the fakes.

According to friends, Obbink displayed no obvious religious convictions. Nor did he have much patience for people whose faith skewed their judgment. “People try to date [Oxyrhynchus papyri] earlier than they really are, because they want Christianity to start earlier than it does,” Obbink told a New Zealand magazine in 2005.

But something happened in the presence of his new patrons. He fawned over the Greens’ aspirations, writing to Scott Carroll in January 2010 that he looked forward “to the flourishing of your commendable undertaking.” He closed emails, as his new benefactors did, with the sign-off “Blessings.” And according to a devout former museum official, he bowed his head and prayed before meals in so “theatrical” a way that, even among evangelicals, he was “the most visibly pious person at the table.”

In early 2012, a few months after their meeting at Christ Church, Obbink invited Pattengale to London to show him a batch of papyri that had come up for sale. The men were steps from Sotheby’s—where Pattengale thought they were going—when Obbink turned down a narrow alley to the small, cluttered apartment of a 30-something Turk, who answered the door in a Yankees jersey.

Pattengale would later learn that the man, a dealer named Yakup Eksioglu, was suspected by scholars of illicitly trafficking papyri. Eksioglu had begun selling antiquities on eBay, under a series of usernames, in 2008, around the time social-media accounts placed him in Egypt. When Roberta Mazza, an Italian papyrologist, grilled Eksioglu about the source of his fragments in 2017, Eksioglu threatened her. “Always look at the back when you walk,” he wrote in a WhatsApp chat she later sent me. He alluded to an attack in Europe in which acid had been thrown in victims’ faces. (Eksioglu says that his antiquities business is fully legal and that if threats to Mazza came from his phone, they were perhaps sent by some students he knew, as “humor.”)

Eksioglu talked on his cellphone behind a beaded curtain as Obbink showed Pattengale a sixth-century Coptic fragment from First Corinthians, for which Eksioglu wanted $1 million. Almost as odd as the meeting’s setting, Pattengale told me, was Obbink’s eagerness for the Greens to buy: “He contacted me not long afterwards to see if we were moving forward, and wondered why we weren’t, and couldn’t believe we weren’t.”

Professor Jeff Fish was in his office at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, in the fall of 2010 when he got a voicemail. The caller was someone named Scott Carroll, who asked whether Fish and his students might like to study papyri from the Green Collection.

Fish had never heard of Carroll or the Greens, much less any new cache of unstudied manuscripts. He might have written the whole thing off as some kind of prank had Carroll not dropped the name Dirk Obbink.

Fish revered the Oxford professor, as much for his scholarship as for the role he’d played in Fish’s own career. Fish had been foundering on his doctoral thesis at the University of Texas in the 1990s when Obbink—with whom he’d taken a summer papyrology class at Oxford—steered him toward a new topic and opened doors to closely guarded Italian papyri.

That someone of Obbink’s renown might partner with a scholar Fish had never even heard of was almost unbelievable. Fish wrote to his old mentor to see whether any of it was true.

“It would be great if we could work together with Scott Carroll on this,” Obbink replied. “I recommend him to you highly.”

Though Fish didn’t know it, Baylor’s Institute for Studies of Religion had already signed on as the home of the Green Scholars Initiative. Baylor administrators were smitten enough with Carroll—and the excitement the Green Collection was generating among students—that they offered him a $100,000 annual stipend and the title “research professor,” though he taught no courses and published no research.

Carroll struck many Baylor professors as less scholar than ringmaster—or “circus act,” as one put it. He showed up with suitcases full of antiquities, passing them around to astonished professors and students. But nothing made more of an impression than the macabre show he would put on in the classics-department lounge.

In the age of the pharaohs, mummified corpses were fitted with masks made of cartonnage, a kind of papier-mâché fashioned from plaster, linen, and discarded papyrus. Nineteenth-century archaeologists discovered that papyri could be extracted from the masks by dissolving the plaster, then carefully peeling apart the wadded texts.

The technique—known as “dismounting”—was clever. But because the ancients made cartonnage from waste papyrus (receipts, notes, and other ephemera), it produced few major literary discoveries. The likelihood of Christian finds was almost nil: Egyptians had ceased using papyri in mummy masks before Jesus’s day. By the 1960s, the practice of dissolving another culture’s death masks on the off chance of finding a manuscript had been all but abandoned, as much for ethical reasons as for the lackluster results.

Scott Carroll, however, presented himself as a modern-day maestro. Where others found dreck, he found gold. “Everything has to be done just right,” including water temperature, drying technique, and the particulars of “enzyme action,” he once told a seminary audience. “I dare someone to try to do it on their own, because they’ll waste hundreds of thousands of dollars if they don’t know the process.”

On January 16, 2012, Carroll gave Baylor a glimpse of how it was done. He filled a sink in the classics lounge with warm water and Palmolive dish soap, plunged a mummy mask into the suds, and began swishing it around. Then he withdrew a wet fragment and presented it to awestruck students.

“He said, ‘Whoa, now take a look at this, and see if you can read it,’ ” recalled David Lyle Jeffrey, a medieval-Bible scholar and former Baylor provost who helped manage the school’s relationship with the Greens. The fragment turned out to be a piece of Paul’s Letter to the Romans. “The kids were bamboozled: ‘Wow! Wow!’ ” It was the kind of eureka moment any professor might hope to inspire in undergraduates.

Jeffrey might have been just as floored, were it not for something he’d noticed when students were first gathering in the room.

Before his demonstration, Carroll had discreetly set a piece of papyrus beside the sink, and Jeffrey had glanced at it. When Carroll withdrew the wet Romans fragment from the mummy mask, Jeffrey recognized it as the piece he’d seen beside the sink. Carroll, he realized, had only pretended to pull it from the mask.

Two days later, Hobby Lobby President Steve Green went on CNN to talk about the Romans fragment, which he presented as the oldest known copy of the Pauline epistle. “This has just been discovered in the past 48 hours,” Green said. In truth, an internal review of sales records would later conclude, Hobby Lobby had purchased it 18 months earlier—from Dirk Obbink.

Though it wasn’t publicly known, Obbink served as more than just an academic consultant to the Greens: Josephine Dru, a former papyrus curator for the Museum of the Bible, told me he was one of their biggest suppliers of papyri. From January 2010 to February 2013, Obbink sold the family more than 150 papyrus fragments—for a total of between $4 million and $8 million, according to a source who has seen the figures and described them to me as a range. (Jeffrey Kloha, the Museum of the Bible’s chief curator, didn’t dispute those numbers, but estimated a total closer to the low end of that range.)

Scott Carroll may have claimed that Obbink had “no agenda whatsoever,” but in fact Obbink had several. He was acting as a scholar, an adviser, and a seller: The first owed allegiance to the truth, the second to his clients, the third to his own bottom line.

Simon Burris, who taught Greek poetry at Baylor, had shown up at the mummy-mask dissolving that January less out of scholarly interest than to take part in the life of the department; lecturers like him did well to show their faces to the tenured faculty who decided whether to renew their annual teaching contracts.

Burris found a spot at a table where Carroll was drying papyri he’d pulled out of the sink, but soon felt his head spinning. Before him was a small Greek fragment with four-line stanzas in an Aeolic dialect—a hallmark of Sappho, the sixth-century b.c. poet from the island of Lesbos, famed for her passionate depictions of love. Sappho is as revered by classicists as her writings are scarce; just one complete poem and fragments of some others survive, many of them from Oxyrhynchus.

Burris quickly spotted other pieces—still wet—bearing the same Sapphic markers. He ran their surviving words through a search engine: They not only overlapped with known Sappho poems, but filled in previously unknown lines.

“I was gobsmacked,” Burris told me. “I think I said an expletive or two—‘holy moly,’ except without the moly.” He remembers Carroll glancing at him with a grin: “Oh, did you find something?” The lounge became standing-room-only. Burris gave an impromptu speech about the poet’s work. One professor was in tears.

Burris was a lecturer with relatively few publications. But here he was, making a find worthy of international headlines. For all kinds of reasons, he wanted to believe it.

But something felt off. The Sappho pieces had been laid out in such a way that even a non–Sappho expert like him could spot several in just minutes. (He would eventually discover some 20 of them.) He wondered: Did Carroll somehow know what was in the mask before he’d disemboweled it?

“I am presently in contact with our PR firm” in hopes of “a press release on this,” Carroll wrote to students later that day. But no press release came, and miraculously, word of Burris’s find never leaked.

Two months later, according to Jeffrey, Carroll told Baylor that if it wanted continued access to the Green Collection, he’d need a bigger paycheck. (Carroll says he never asked for a raise and that Jeffrey was simply unhappy with how much Baylor was already paying him.)

The jarring request, together with his concerns about the mummy masks, prompted Jeffrey to take a closer look at Carroll’s résumé. He discovered that half a dozen books Carroll claimed to have written didn’t actually exist.

Carroll was fired by Baylor and the Greens in May 2012, but by then they no longer needed him. Both had begun strengthening ties to an Oxford professor who couldn’t have seemed more different.

In most respects, Obbink was indeed Carroll’s opposite: a professor at one of the world’s most prestigious universities, aloof, reserved.

Yet in the decade after Obbink’s genius grant, a view had taken hold among some colleagues that he’d failed to live up to the high expectations. Some thought he’d spread himself too thin, chasing every short-lived opportunity rather than pursuing the sort of single-minded research that had produced Philodemus on Piety: Part 1, the 1996 opus that had vaulted him to the highest echelon of classical scholarship. The MacArthur Foundation had noted that Part 2 was due out in 2003. Seventeen years later, it remains unpublished.

He struggled even to finish articles. In a crowded elevator at a classics conference, when one academic editor jokingly asked how many others were waiting for a piece of writing from Obbink, half the hands went up.

As the years passed, Obbink seemed more interested in monetizing his work—a common enough practice in the sciences, but rare in the humanities. In 2011, he founded a start-up with Chinese entrepreneurs and Oxford seed money to design desktop manuscript scanners, an enterprise that U.K. business records show has hemorrhaged money. (Pattengale told me that boxes of the scanners were piled, unsold, along the walls of Obbink’s office.) In 2012 came Oxford Ancient, and in 2014, an antiquities business called Castle Folio, which he co-founded with a Michigan man named Mahmoud Elder.

By 2013, the Museum of the Bible was paying Obbink $6,000 a month, twice the top rate for other academics in its scholars initiative.

At events sponsored by the Greens, Obbink, at times in a white lab coat, dunked wedges of mummy cartonnage in soapy water. “He says, ‘This is what scholars do,’ ” recalled Jeremiah Coogan, a student who attended one. “We got this spiel about ‘This is where you discover New Testament papyri’ ”—a line that Coogan, like other scholars, soon recognized as dubious.

Obbink had once kept hundreds of Oxford’s uncataloged mummy masks in his rooms, as a favor to the university, which was short on storage. But a longtime colleague told me he’d never seen Obbink perform a dismounting. “This sort of thing never took place in his university teaching.”

Not that Obbink hadn’t thought about it. In a German newspaper interview in 2005, he’d fantasized about the potential bounty of poems and plays. But, as the newspaper reported, “experts no longer use such methods.” Five years later, Obbink appeared to have abandoned any qualms: “Suitable for dismantling/dissolving,” he wrote in the sales paperwork for a mask Hobby Lobby bought from him in 2010.

It was one of some 20 masks Obbink sold the Greens. A source who has seen the figures told me that on top of the $4 million to $8 million he charged for papyri, the family paid him $1 million to $2 million for a host of other antiquities. Among them was a medieval Latin manuscript titled “On Stolen Things.”

In early 2014, headlines appeared across the world: Obbink had discovered a pair of breathtaking new Sappho poems—on a piece of papyrus salvaged from a mummy mask. “For a couple of months, it was just me and a girl named Sappho—nothing between me and the text,” Obbink said on BBC Radio. “It was like being shipwrecked on a desert island with Marilyn Monroe.”

But Obbink declined to name the papyrus’s owner or to release its provenance paperwork. In a New York Times op-ed, Douglas Boin, a historian at Saint Louis University, called Obbink’s secrecy “disturbingly tone deaf” at a time of “catastrophic” looting in the Middle East. The next year, Christie’s produced a 26-page brochure offering the two Sappho poems for sale “by private treaty,” a transaction in which an auction house quietly approaches prospective buyers rather than hosting a public sale.

Obbink eventually told a convoluted tale about an anonymous London businessman who had bought cartonnage at a Christie’s auction in 2011, dissolved it, and brought extracted papyri to Obbink, who discovered the two Sappho poems. The businessman then put some 20 small scraps that had also been pulled from the cartonnage—“being not easily identified … and deemed insignificant”—on the market. By chance, an intermediary dealer sold them to the Green Collection, where Obbink picked them out as yet more Sappho.

Brent Nongbri, a Christian-manuscripts scholar, has identified no fewer than six different accounts of provenance put forward by Obbink, Carroll, or Bettany Hughes—a British broadcaster who has featured Obbink on several of her TV and radio shows. None of those accounts included the one detail witnessed by a large group of people: Simon Burris’s identification of the smaller Sappho pieces in Baylor’s crowded classics-department lounge in 2012.

Sources close to the Greens told me that some of the Sappho pieces Burris “found” that day are visible in photos dated December 7, 2011, more than a month before Carroll pulled them from the soapy water at Baylor. The images appear in an invoice for papyri that the Greens bought on January 7, 2012. The seller was Yakup Eksioglu.

In a WhatsApp chat this February, Eksioglu told me that he was, indeed, the source for all the Sappho fragments—the 20 small pieces “discovered” at Baylor, and the large sheet with the two new poems. The claim that they had come from cartonnage purchased at a Christie’s auction in 2011 was a “fake story,” he said. When I asked why some of the pieces looked, in photos, like they had been embedded in cartonnage, he suggested that they had been staged: “This is a very simple method, you can do it by wetting.” Eksioglu said the Sapphos had belonged to his “family collection” for at least a century.

When I asked for corroboration, he said he didn’t want to bother his relatives and that in any case no one but him knew anything about it. In our many exchanges, Eksioglu trafficked in conspiracy theories and made statements that he later acknowledged were lies. But even if only the documented claims are true—that he sold the Greens the smaller Sappho scraps—they expose Carroll’s Baylor demonstration as a con and discredit key parts of Obbink’s provenance story.

When I told Carroll what I’d discovered, he acknowledged planting the Sappho and Romans fragments in the mask at Baylor that day. His aim, he said, was to teach students how to identify papyri, not how to dismount a mask. Unsure of what he’d recover from the mask, he decided to mix in some exciting pieces from the Green Collection. “At the time, I didn’t feel that it was duplicitous.”

Representatives for the Greens knew long ago that Eksioglu was the source of the new Sapphos. But they stayed mum even as questions mounted. “It’s interesting that hardly any Sappho has surfaced for decades and now there’s plenty,” one senior Museum of the Bible official wrote to two others on July 11, 2012. Of Eksioglu, the official added, “You’re likely both aware that he’s been the main conduit for much of the best stuff surfacing.”

“There-in is the potential issue,” one of them replied. “Where is it coming from?”

Though housed at Oxford, the Oxyrhynchus Papyri are owned by the Egypt Exploration Society, the London charity that financed their excavation. Public criticism of Obbink’s Sappho dealings deeply unsettled the EES; the collection’s general editors weren’t supposed to have anything to do with buyers or sellers of antiquities. At a meeting in London in July 2014, EES officials gave Obbink an ultimatum: Cut ties with the Greens or lose his editorship.

That night, after Obbink returned to Oxford, he went to the hotel where Jerry Pattengale and Steve Green were staying during a summer session of the Green Scholars Initiative. They took seats on an outdoor patio, and Obbink told them of the EES’s mandate.

“He was sweating profusely,” Pattengale recalled. If the EES shut Obbink out of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, he would lose the raison d’être for his position at Oxford—and maybe his position along with it.

Pattengale pitched the Greens on endowing a chair for Obbink at Oxford, to keep him at the university even if he lost access to the collection. “This was simply to treat someone well who had been so helpful,” Pattengale told me. But he was overruled; Cary Summers, then president of the Museum of the Bible, saw a faculty job for Obbink at Baylor as a better contingency plan. “It was disingenuous,” Pattengale told me. “It would be the museum funding Baylor to fund him”—masking his ties to the Greens and thereby maintaining his access to the Oxyrhynchus collection, even if he spent part of the year in Texas. (Summers did not respond to multiple interview requests.)

Obbink told the EES that he’d broken with the Greens. In truth, sources told me, the Museum of the Bible continued to finance his projects and pay him the $6,000-a-month stipend. If the EES found out, Obbink might need a new job, fast.

In September 2014, two months after the EES ultimatum, Obbink bought a faux medieval castle a short drive from the Baylor campus. Fish, the Baylor classicist, was dumbfounded.

The 124-year-old Cottonland Castle, built of sandstone, Carrara marble, and Honduran mahogany, was a wholly out-of-place structure, bordered by a used-car lot and blighted by water damage and graffiti. When I visited Waco last fall, people told me that teenagers had a Halloween tradition of breaking into the vacant building and sneaking through the dark to its top floor.

Did Obbink plan to live in the castle? Was he hoping that a showy display of civic goodwill—the restoration of a notorious Waco eyesore—would improve his prospects for a full-time job offer from Baylor? No one at the university seemed to know.

“I think it reminded him of Oxford,” Tom Lupfer, the renovator Obbink hired, told me. Lupfer showed me the plans: underground garage, elevator, spiral staircase leading from sundeck to swimming pool, pool house with changing rooms. Lupfer warned Obbink that the work would take a few years and cost as much as $1.4 million. Obbink didn’t flinch, but Lupfer wondered how anyone on an academic salary could afford such extravagance.

In November 2015, a video appeared on YouTube, filmed on a smartphone from the pews of a church in Charlotte, North Carolina. From the pulpit, where he was addressing a conference of conservative Christians, Scott Carroll spoke of seeing a Gospel of Mark from the first century “at Oxford University at Christ Church College … in the possession of an outstanding, well-known, eminent classicist … Dirk Obbink,” who thought the papyrus might date to as early as a.d. 70—the same year most scholars think the gospel was first composed.

This was no longer Daniel Wallace telling a vague, secondhand story on a debate stage. This was an eyewitness with names, dates, and places. The video so unnerved the Egypt Exploration Society that it began a review of all its unpublished New Testament papyri. It learned that one of Obbink’s researchers had found a small fragment of Mark in its collection in 2011, a piece photographed by a curator as early as the 1980s but never before identified.

Was this the discovery that Wallace had announced at the University of North Carolina—and that Carroll had confirmed in the church video nearly four years later?

Confronted by the EES, Obbink admitted to having a fragment of Mark from Oxyrhynchus in his office and showing it to Carroll. But he insisted that he’d never said it was for sale. The EES instructed him “to prepare it for publication as soon as practicable in order to avoid further speculation about its date and content.”

Obbink could no doubt foresee the consequences of publication: The moment images of the fragment became public, Pattengale, Carroll, and Wallace would recognize the papyrus as the one he’d allegedly offered to the Greens half a decade earlier. They would notice he’d published it in the official book series for EES papyri—exposing it as never his to sell. Perhaps most distressing, they’d see Obbink’s new dating: In a book of serious scholarship, he’d assign their supposed “first-century Mark” to the late second or early third century, making it far less remarkable.

In 2016, the EES declined to renew Obbink’s position as general editor and took away his key to the papyrus room. He could no longer work there unless supervised by Daniela Colomo, the collection’s curator. The next year, as the deadline for Obbink’s editio princeps approached, it looked to his editors as though he might never finish. Unwilling to brook further delay, the EES enlisted Colomo and the collection’s researcher, Ben Henry, to complete it for him.

Meanwhile, new curators at the Museum of the Bible began making disquieting discoveries about the Greens’ papyri. David Trobisch, who directed the museum’s collection, called Eksioglu while on business in Istanbul. The dealer picked Trobisch up at his hotel at 2 a.m., drove him to a high-rise apartment, and plied him with cigars and whiskey. Trobisch asked where Eksioglu had gotten the papyri he sold the Greens. “He had no records, there was nothing, he couldn’t help me,” Trobisch told me.

But Eksioglu hoped Trobisch could help him. The dealer set cardboard boxes containing at least 1,000 fragments of papyri on his kitchen table, in hopes of another sale.“Where is it from?” Trobisch asked. Eksioglu mumbled something about war and Syria, then mimicked locals stubbing their toes into the ground, stumbling on antiquities.

“This is over,” Trobisch replied. (Eksioglu denies meeting Trobisch, and says that a student had gone in his stead.)

Later that day, when Trobisch met with another of the Greens’ Turkish papyrus suppliers, “he wanted to know whether I came with the police.”

In December 2017, Trobisch and his soon-to-be-successor, Jeffrey Kloha, traveled to Oxford to ask Obbink about the sources of his papyri. “He said he didn’t have [the provenance paperwork] in his office, he would check later, he would forward them to me later,” Kloha told me. “He never produced anything.” The Greens broke all ties with Obbink the next month.

When the Mark fragment was finally published, in April 2018, in the book The Oxyrhynchus Papyri Vol. LXXXIII, it ignited exactly the scholarly firestorm anyone might have predicted. On his influential blog, Brent Nongbri wrote, wryly, “Seems like there is a bit more to the story.”

In June 2019, Michael Holmes, who replaced Pattengale as the director of the scholars initiative, flew to London to meet with leaders of the Egypt Exploration Society, who remained skeptical that Obbink, whatever his other shortcomings, might have sold Oxyrhynchus papyri.

Over lunch at a private club, Holmes pulled out a purchase agreement between Hobby Lobby Stores Inc. and Dirk Obbink. Co-signed by the Oxford professor on February 4, 2013, it showed that Obbink had sold the company not just the Mark papyrus, but also fragments of the Gospels of Matthew, Luke, and John. In the contract, Obbink describes the manuscripts as his personal property, vows to “ship/hand carry” them from “Oxford Ancient,” and dates all four to a historically unprecedented “circa 100 AD,” making each a one-of-a-kind worth millions.

When EES officials saw the contract, Holmes told me, “any uncertainties they had evaporated very quickly.” They banned Obbink from the collection.

The Museum of the Bible began sending to the EES images of every papyrus the Greens had purchased—from any seller. Comparing them against the society’s own photographic inventory, EES officials spotted 13 of its biblical fragments. From written descriptions provided by Hobby Lobby, it identified four more: the gospels that Obbink’s sales contract dated to the first century, though none, the EES said, were in fact that old.

Fifteen of the EES’s fragments had been sold to the Greens by Obbink, for more than $1.5 million, a source who has seen the figures told me. Among them was the Romans scrap Carroll pretended to pull from a mummy mask at Baylor in 2012.

The Greens bought the two other EES fragments from the family business of Alan Baidun, a Jerusalem dealer who appeared to have acted as a middleman for Obbink. (Baidun did not answer multiple emails and phone calls, but has previously denied wrongdoing through a spokesperson.)

The EES soon discovered another half-dozen of its papyri in the collection of a wealthy California collector named Andrew Stimer, who had previously sold the Greens four Dead Sea Scrolls that the Museum of the Bible later deemed forgeries. (Stimer disputes the museum’s forgery findings.)

Stimer, who leads an evangelical ministry called Hope Partners International, said he purchased two of the fragments in 2015 from a “Mr. M. Elder of Dearborn, Michigan,” a seeming match for Obbink’s business partner. When scholars saw images of those fragments—from Romans and First Corinthians—they realized the Museum of the Bible owned adjoining pieces from the same leaves. Someone appeared to have cut up scriptures that, according to EES photos, had been intact at Oxford. “Mr. M. Elder” had sold one pair of cuts to Stimer, and Obbink had sold the other to the Greens. (Mahmoud Elder declined to comment, invoking what he called a “client non-disclosure agreement.”)

An inventory of Stimer’s collection, provided to me by a source, states that two other papyri—from Exodus and Psalms—had been “deaccessioned,” or sold off, by seminaries in Berkeley, California, and Dayton, Ohio. It was a lie: Both fragments belonged to the EES. (Stimer told me he was “blindsided,” has returned the EES fragments, and is trying to recover the “substantial sums” he paid. Obbink, he said, had listed the Berkeley and Dayton seminaries as their source in a scholarly report that came with the purchase.)

For most of the stolen papyri, the EES’s corresponding inventory cards and photographs were also missing. The thief, it seemed, had sought to cover his tracks by erasing evidence of the papyri’s existence. In a collection of some half a million pieces, perhaps they’d never be missed.

But the thief miscalculated: Copies of the inventory existed in various locations, including University College London.

Drawing on such backups, the EES said it has so far identified 120 papyri that “appear to be missing, almost all from a limited number of folders.” In what might well be British understatement, it warned “that a few more cases may emerge.”

On November 12, the EES reported its findings to the Thames Valley Police. On March 2, the police detained Obbink for questioning on suspicion of theft and fraud. As of press time, no charges had been filed.

“The allegations made against me that I have stolen, removed or sold items owned by the Egyptian Exploration Society collection at the University of Oxford are entirely false,” Obbink said in a statement this past October, four days after the EES and the Museum of the Bible announced the results of a preliminary joint investigation. “I would never betray the trust of my colleagues and the values which I have sought to protect and uphold throughout my academic career in the way that has been alleged.” He hinted, darkly, that he may have been framed, but declined to elaborate.

A few days later, in the second week of Oxford’s fall term, Obbink was relieved of his teaching duties.

I traveled to Oxford later that week and rang the doorbell at a comfortable-looking but hardly lavish house with a small swimming pool at the end of a leafy lane. When Obbink opened the door, he was wearing black jeans, slip-on leather shoes, and a tan shirt with stylized military epaulets.

I said I was there because I wanted to hear his side of the story.

“I’d like to tell it,” he said, with an almost preternatural calm, “but I’m under a duty not to speak about the matter while it’s under investigation” by Oxford.

In April, I sent Obbink and his attorney a detailed list of questions. His attorney responded with three minor clarifications, but said that Obbink was otherwise unable to comment because he owed “confidentiality to Oxford during its ongoing internal process.”

If Obbink’s relationship with the Greens had a fatal flaw, it was that he needed it to stay secret, whereas the Greens wanted to shout it to the world. “By far and away, Dirk is the most strategic friend and supporter of all that we are doing,” Carroll wrote to Steve Green in a June 2011 email.

In negotiations with Hobby Lobby for the sale of the four “first-century” fragments, Obbink had demanded a set of highly irregular contract clauses: There was to be no public announcement of the acquisition; Obbink could never be named as the seller; and the fragments would stay in his office at Oxford for four years—after which there would be what he called “a kind of ‘shared custody’ with ‘visitation rights.’ ”

In hindsight, Pattengale allowed, the whole arrangement “was kind of far-fetched.” But at the time, all he could think of was how much he wanted Hobby Lobby to own a gospel fragment from so close to Jesus’s day. He emailed his superiors, pressing them to meet Obbink’s demands; they eventually did.

When I met Jeff Fish on the Baylor campus last fall, he wore a look of anguish as he talked about a man he’d once venerated. What hurt most was a sense that Obbink had tried to play him for a patsy—assuring him of Carroll’s bona fides, and encouraging him to publish papyri the EES would later claim as stolen.

“I was used,” Fish said.

Baylor, which had brought Obbink to campus a few times to give lectures and short seminars, had been on the cusp of offering him a full-time, tenure-track job in 2018 when Fish intervened. “It would be a terrible mistake,” Fish warned the classics chairman. Obbink never got the offer.

His payments to Lupfer, the renovator of his Texas castle, soon fell into arrears. In February 2019, he sold the property to Chip and Joanna Gaines, the Waco couple behind the HGTV series Fixer Upper. Factoring in the $200,000 he had spent on renovations, Obbink lost roughly $100,000 on the sale, according to Lupfer.

On March 26, Steve Green announced that he was giving 5,000 of his papyri to Egypt. It was an admission that virtually every papyrus in his collection lacked sufficient evidence of not having been stolen, looted, or acquired by other improper means. For the same reasons, he said, he was repatriating 6,500 clay relics to Iraq—on top of the 3,500 Iraqi antiquities Hobby Lobby had surrendered to settle a 2017 federal smuggling case.

Green and his museum have sought to portray themselves as chastened by their early stumbles and determined to make amends—both by coming clean about their failures and by making institutional changes. “I trusted the wrong people to guide me,” Green said, “and unwittingly dealt with unscrupulous dealers in those early years.”

Scholars have praised the latest reforms. But Green’s efforts to deflect blame have rung hollow in some circles.

In 2010, early in his collecting blitz, Green had attended a presentation that Hobby Lobby commissioned from Patty Gerstenblith, a DePaul University professor who is one of the world’s foremost experts on cultural property law. “I warned him,” Gerstenblith told me, “and he proceeded anyway.” With hundreds of millions of dollars of spending power, Green had all the leverage to ask hard questions about provenance—and to order investigations—before handing his money over to dealers. But he never did.

In the Obbink case, Green and his representatives have cast themselves as the unsuspecting dupes of a mastermind. Green told me he’d failed to see the conflict in Obbink’s dual roles as adviser and seller because of his “stellar reputation and standing in the scholarly community.” He added, “I would never intentionally buy anything forged or stolen.”

Green has returned the stolen Oxyrhynchus fragments to Oxford, and in 2018, he told me, Hobby Lobby asked Obbink to refund the money it had paid him for the four “first-century” gospel fragments.

“Professor Obbink provided assurances many times that he would pay us back, and asked for time, which we patiently gave him,” Green told me. He said Obbink reimbursed $10,000 last summer but stopped communicating after news of the alleged thefts broke last fall.

Until Oxford, the EES, or the police reveal more, many questions will remain unanswered. But in the eyes of some devout critics, the last chapter of this saga will be written by a higher authority. “Believers in the truth of the Bible cannot act like pirates,” Peter Costello wrote last year in The Irish Catholic, Ireland’s largest religious newspaper. “If they wish to help establish the truth they must do it through legal channels … God’s truth deserves nothing less.”

This article appears in the June 2020 print edition with the headline “The Case of the Phantom Papyrus.”