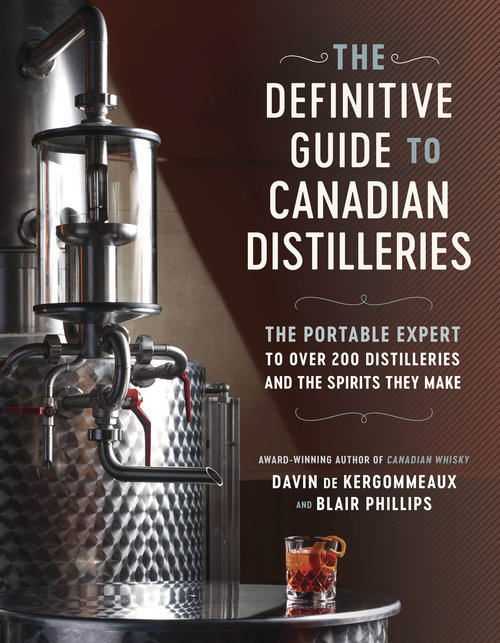

Having solidified his standing as the world expert on Canadian whisky via, among other things, the publishing of Canadian Whisky, Canadian author Davin de Kergommeaux, along with coauthor Blair Phillips, recently released The Definitive Guide to Canadian Distilleries. This new book shines the spotlight on over 200 Canadian distilling operations coast to coast, while at the same time offering readers an in-depth look at the past, present and possible future of the Canadian distilling industry. I had the opportunity to talk to de Kergommeaux not only about the book, but about his passion: distilling in Canada.

How did the idea for this new book come about? Was it just sort of a “logical next step” having reviewed whisky distillers across Canada in your previous book, or was there something more?

A little bit of both. When I updated my Canadian Whisky book, it made sense to include the newer distilleries that were making whisky. At the same time, I could see all kinds of distilleries that made other spirits coming on line as well. The enthusiasm of these new distillers with their big plans and sometimes tiny budgets was genuinely inspiring. The more I learned about them, the more I realized there was an inspiring story to tell.

Did you contact Blair, did he contact you, or were you both at an event and started batting ideas around?

Blair interviewed me back in 2012 for a story he was writing for Zane Lamprey’s Drinking Made Easy. I mentioned I had a whisky book coming, so he showed up for the Toronto launch and came over and introduced himself. He sent me a few queries for stories he was writing about Canadian whisky and I realized that he told a pretty good tale and I enjoyed his humour and references to pop culture. I asked if he’d like to collaborate on a few pieces for Whisky Magazine and before long we were on the road together, writing a whisky travel series. I learned he also has a great palate for and interest in other spirits. When he suggested we take our adventure series to the next level and write a book together, it seemed like a natural fit.

The coverage in The Definitive Guide is extensive – how long did it take from the time your publisher gave you the go-ahead to when it came off the press?

The publisher and I discussed the book in 2017 and we signed an agreement in the summer of 2018 after we had a fully developed proposal that was agreeable to both. The book was released on March 31 this year, so 18 months from the deal to publication. However, Blair and I actually began visiting distilleries regularly and gathering information for a book as far back as July 2014.

Did you both physically travel across the country to do research, did you divide the country up and each covered a certain area, was it mostly done electronically, or bit of everything?

We started out working together visiting distilleries in the Atlantic provinces, with stops in Ontario, Manitoba and Alberta. Once we had a deadline though, we split up. The number of distilleries had doubled and we realized we would have to work somewhat independently. One or both of us visited most of the distilleries, though, for some, we relied on telephone calls and email exchanges. We each edited the other’s work, so we worked it into one voice and one style. So, some of the research was conducted independently, but the writing was a genuine collaboration.

What things surprised you most about the state of Canada’s distilling industry?

The most surprising thing is the vibrancy of the industry – large distillers and small, the speed at which it is expanding and the tremendous diversity of spirits made right here in Canada.

Canada is well known as a whisky producer as you’ve documented, but is there another spirit category that you see Canada becoming equally well known for producing?

I’d love to say vodka because a change in federal regulations that allows vodka distillers to use any agricultural produce as a feedstock has led to some exciting new spirits. We have really interesting vodkas being made from such diverse sources as blueberries, honey, maple sap, milk permeate and apples. And each retains subtle, elegant traces of its source. However, I think where Canada, and Quebec especially, is really distinguishing itself is in gin.

What differentiates what the craft/artisan distilleries are doing and/or experimenting with compared to what the “big guys” are doing? Is it mostly about innovation as far as the smaller operations go, or do you think all Canadian distilleries share an innovative streak?

Innovation is important to both but practiced differently. For the small distillers, there is a lot of doing things differently because they can, because they have to, or just to see what happens. Innovation is huge with the large distillers too, but the approach is more strategic. They have the resources, experience and capacity to plan and execute long-term trials and experiments, and they have the luxury that not every experiment need work out.

In your opinion, what is the most positive aspect of the Canadian distilling industry?

Canada has a long history of making outstanding spirits, but for the most part these tend to fly under the radar. With the emergence of the craft distilling movement, finally Canadians are taking notice of homegrown spirits and this benefits all distillers. Suddenly, Canadian spirits are in the news regularly and drawing glowing reviews. Canada’s “best-kept-secret” status is no more.

And, of course, the flip side: what do you feel is not happening the way it should?

Canada’s spirits industry is severely impeded by outrageous tax rates. In many jurisdictions smaller distillers get a break – as long as they remain small – but, large distillers do not. This means the multi-nationally owned large distilleries that make 99 percent of our spirits and almost all of our exports, have little incentive to make capital investments in Canada when the same money invested in other countries generates higher returns. This, in turn, hurts the Canadians who grow the grain and those who turn it into spirits. People forget that even the largest distilleries make considerable contributions to their local economies.

Add to that, regulations that cap production levels for small distillers to qualify for tax breaks mean they have to change their business model if they want to grow past a certain point. This is one reason some truly beautiful spirits are available only in their home province. Producing larger volumes so they could sell in other provinces or abroad would cost them their lower taxation rates. This in turn would make their products too expensive at home and in export. As much as the politicians want to smile and take credit for what really are small advances, many of them simply do not have a clue how much more Canada’s distilleries could inject into their local economies.

The most surprising thing is the vibrancy of the industry.

Davin de Kergommeaux

What do you think is behind this weird mindset that spirits are somehow “the worst alcohol” as far as the “social responsibility” aspect goes? Governments seem willing to at least consider greater distribution of wine, beer and cider, but spirits are strictly off the table in this respect.

Please don’t get me started. A drink is a drink is a drink. There is absolutely no logical explanation for charging different excise tax rates on beer, wine and spirits. If all alcoholic beverages paid the same tax rate based on the alcohol content of the product, both producers and consumers would be much better served. And directly to your point, there is absolutely no redeeming reason that in Ontario, for example, grocers can sell beer and wine, but not liquor. This is prohibition-era thinking based on faulty logic and in practice, forcing them to visit two different location for a full selection of alcoholic beverages, reduces the choices available to consumers. A drink is a drink is a drink.

Do you find it ironic that government liquor monopolies make their highest margins off spirits but seem unwilling to expand distribution?

I suppose you could say ironic, but I see it as just bad business. If the goal is to generate income for the government, then logically, spirits should be as readily available as beer and wine. What happens in LCBO boardrooms is not really clear, but we sometimes hear of strong lobbying by LCBO workers’ union to maintain union jobs (and their higher salaries) by restricting sales to just government stores. However, we also hear that even though they pay them union wages, LCBO managers can be quite arbitrary in assigning hours to staff. One has to wonder if LCBO staff are really better off in the long run than grocery store workers with regular hours.

It would also help if government-run stores embraced locally-made spirits instead of having them compete with multi-million dollar marketing budgets for shelf space. Look at Quebec, for example. One of the reasons why you see a decent range of Quebec spirits available at the SAQ is because consumers demand them. If it were up to the boards, they wouldn’t make the effort.

Compared to that of wine and, increasingly, beer, where do you peg the “average consumer’s” knowledge of spirits overall?

Consumers are becoming better educated about spirits by virtue of spirits increasing presence in the media. At the same time, some of the newer distillers are doing consumers and the industry a disservice by importing categories and definitions from other countries, that are meaningless here. For example, some distillers are naming their whisky using styles that do not fall within Canadian regulations. Adopting, for example, the American definition of rye when Canada’s definition has been in use for maybe a century longer, does nothing to help differentiate Canadian spirits. In fact, it diminishes them. Similarly, pretending that so-called white rye is whisky is confusing to consumers. I think in time, this will shake out as both distillers and consumers become more informed.

There are cases, of course, where distillers are making spirits that are not widely known in Canada, and here consumers are learning new things about spirits. For example, Bruinwood Estate Distillery’s Advoccat is made from a Dutch family recipe. Winegarden Estates and their German eau-de-vies and Steinhart’s London Dry Gin are nothing but world-class. All of these spirits and many more have a strong connection back to the distillery’s story and teach consumers about spirits without coming across as bastardizing another nation’s style or identity.

If you could do one thing to improve the Canadian distilling landscape for both consumers and producers, what would it be?

Replace the current excise taxes with a single rate, based on volumes of absolute alcohol produced/sold, for all producers of alcoholic beverages of any type. And if the government run stores do not want to give the provincial distillers shelf space, then allow for private stores that will.

You’ve published a book at a not-so-great time to be engaging in any new venture. What have you been doing to get the word out?

Make me cry, why don’t you. I could never have imagined how difficult it would be to get the word out. We had a month-long launch tour planned and it was all cancelled. So now we are using primarily social media to let people know. People can’t buy a book if they don’t know it exists. At the same time, it is very heartwarming and affirming to see how many people with strong social media followings jump right on board, inviting us to “live” online events and posting reviews and such. It is impossible to predict how this will work out, but at least we feel supported by our followers, our community and our publisher.