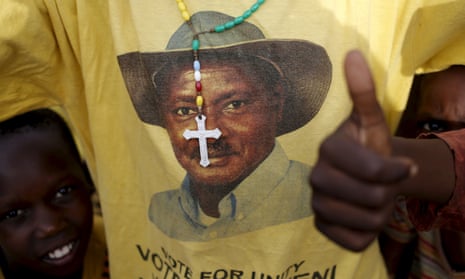

Uganda’s national electoral commission (EC) is once again under intense scrutiny after a messy presidential election that effectively locked out hundreds of thousands of voters in opposition strongholds – to the benefit of Yoweri Museveni, the incumbent.

Museveni, in power for the past 30 years, campaigned on a slogan of “Steady progress”, but, according to many observers, Thursday’s election reeked of democratic stagnation or even regression.

More than Museveni’s widely expected victory, the shambolic exercise has raised questions about the efficacy of elections as a means of choosing leaders in post-military political systems.

National Resistance Movement candidate Museveni won the elections with 60.8%, against 35.4% for Dr Kizza Besigye, of the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC). Former prime minister Amama Mbabazi came third with 1.4%.

As expected, 71-year-old Museveni is revelling in his win, praising the voters and thanking the electoral commission for a good job. In a gloating speech on Sunday, Museveni promised to use the next five years to fight poverty and corruption.

However, both Besigye – Museveni’s former physician – and Mbabazi rejected the results. There was also a terse statement from Maj Gen Mugisha Muntu, Museveni’s former army commander now heading the FDC, who asked Ugandans and the international community to reject the results.

Besigye, who was detained and placed under house arrest as he planned to expose “discrepancies” between the official results and those from FDC polling agents, spoke of “the most fraudulent electoral process in Uganda”.

Mbabazi cited several irregularities, including alleged marking of ballot papers in favour of Museveni, inaccurate tallying by presiding officers, concealment of results declaration forms and late arrival of election materials at polling stations.

The latter was the most eye-catching and inexplicable flaw, especially because it mostly affected opposition strongholds in districts around the capital, Kampala, and key municipalities.

These are highly urban areas where, according to opinion polls, Besigye had his highest approval ratings and Museveni his lowest.

In some polling stations within 4km of the headquarters of the electoral commission, voting started as much as five or six hours late. This led to suspicion by voters – and statements by party leaders – that the flaw was a ploy by authorities to disenfranchise predominantly opposition voters.

The EC chairman, Dr Badru Kiggundu, apologised for the delays and belatedly extended voting hours, but, by then, many voters had either given up and left or were still turned away at the original 4pm deadline.

Moreover, as Mbabazi pointed out, the EC announced the final results without considering nearly 1,800 polling stations, reasoning that Museveni had already surpassed the 50% of votes required for victory.

In their preliminary reports, election observers from the EU and the Commonwealth, as well as from Ugandan civil society, were critical of the EC. They said the commission lacked transparency and independence. The US embassy said the election fell short of international standards. However, many observers from Africa-centred missions generally defended the performance of the commission.

Between 2011 and 2015, Ugandan civil society and political opposition parties carried out nationwide campaigns for electoral reforms. Among other things, they wanted a statutory body – rather than the president – to appoint electoral commissioners for one non-renewable term. They argued that the commission ends up working for and at the behest of the ruling party and the president.

Those proposals were rejected by parliament, which is dominated by Museveni’s NRM party.

With the performance of the EC again under scrutiny, some observers have been quick to refer to the rejected proposals, as well as earlier questions – by the courts – about the EC’s performance in the 2001 and the 2006 elections.

Mwambutsya Ndebesa, a political historian at Makerere University in Kampala, says most of the present complaints about the EC were raised after earlier elections. He says the latest elections showed that as a democracy Uganda had “stagnated or even regressed”.

According to a nationwide independent opinion poll in January, only 40% thought the elections would be free and fair, and 41% believed elections could remove a sitting president. Ndebesa suggests that the performance of the EC will not improve that perception.

“All the past mistakes have been repeated. This is intransigence and it does not augur well for our democracy,” Ndebesa says. “It means the problem is not technical; the problem is deliberate. Management of elections is done in such a way that it is unfair to the opposition.”

For Dr Kabumba Busingye, a leading lawyer at Makerere University, to understand the shambolic election one has to remember something that Museveni repeated in his victory speech on Sunday: that the NRM is a revolutionary party. This, Kabumba says, puts Museveni in the same philosophical bracket as former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi or Ethiopia’s Meles Zenawi.

“For such leaders, because elections are not the way they obtained power, elections cannot be the way they lose power,” Kabumba says, adding that, for people like Museveni, elections serve only to legitimise their stay in power.

Kabumba points out that at least 5 million registered voters did not vote this year, around the same number as did not vote in 2011.

However, he refuses to blame this figure on apathy, saying the stay-away voters include many who desire change – just like those who voted for the opposition.

“They protest against the status quo by refusing to participate,” he says. His prognosis is that after this election, Uganda could see more pro-change voters losing faith in elections.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion