The wife of Lincoln’s secretary of state was a resilient woman who tried to influence politics at high levels, Rochester historians say.

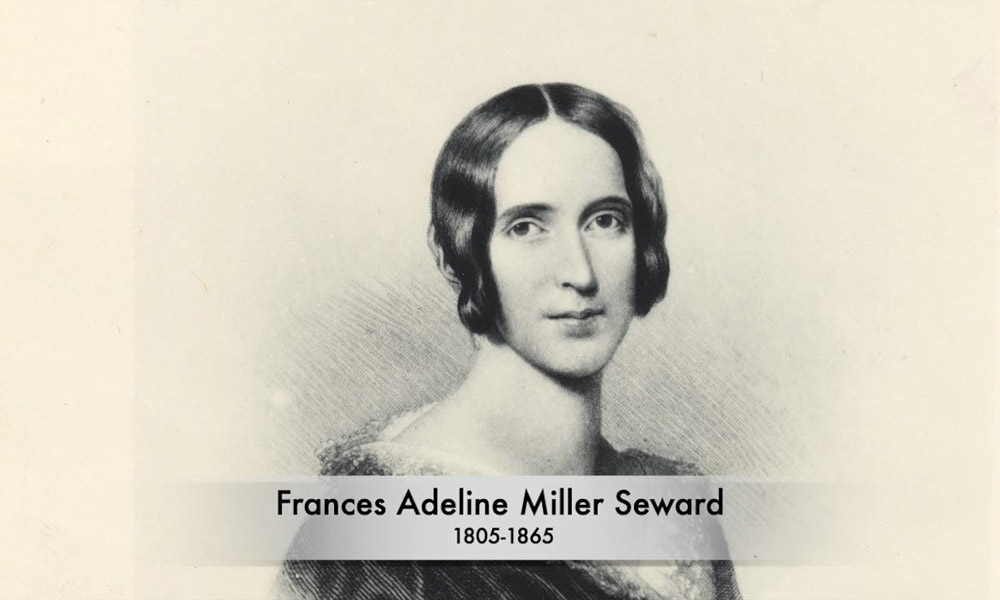

A team of University of Rochester historians says the life of Frances Adeline Seward (1805–1865) deserves a more nuanced and careful reading than her traditional portrayal as the reclusive wife of a 19th-century politician. Doctoral students Shellie Clark, Carrie Knight, and Lauren Davis are using the University’s extensive, firsthand collections of documents of the family of Frances and William Henry Seward, secretary of state to Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, to conduct that re-evaluation.

Seward Video Playlist

Visit the Seward Family Digital Archive video playlist to view more videos about the Sewards and the origins of the Seward Family Digital Archive Project.

The archive is a collaboration between the Department of History and River Campus Libraries at the University of Rochester.

With the help of Sarabeth Rambold, a history PhD student and videography manager for the Seward project, and Demi Robbins ’23, a political science and English major, the students have now produced a video about Frances Seward’s life.

Clark says Seward initially comes off as “a little critical, a little bit judgmental” with a tad of a “challenging personality,” but, having historically been presented as an invalid and recluse, she defies easy characterization.

“She made very kind offers to people; anything from borrowing a tea service to providing a home,” says Clark. While she was up against physical and mental health challenges, most of which had little effective treatment or cures at the time, Frances’s correspondence points indeed to a “rational” and “resilient” 19th-century woman.

Undoubtedly traditional in her approach—Frances believed that wives should influence their husband’s views and serve as their moral compasses, yet all from home and not publicly—she was certainly a more committed abolitionist than her husband. Free from the need to appease political allies and opponents alike, Frances felt, according to Clark, that abolition “was a straight line, that there was no compromise for.”

Letters are part of University’s extensive Seward Family Archive

The three students are reading through four decades of Frances’s letters to and from friends, family, and acquaintances. Their work is part of the Seward Family Digital Archive, which digitizes, transcribes, and annotates the prominent family’s letters, diaries, papers, and documents.

From that collection, they have unearthed a very social woman, one who was friendly and warm, often trying to help those around her.

The letters form part of the Seward Family Archive, one of the most extensive firsthand accounts of 19th-century American political and social life, and the largest and most frequently cited manuscript collections in the University’s Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation Department at River Campus Libraries.

Spanning the 19th and first two decades of the 20th century, the collection offers important insights into the central issues that have shaped the identity of America from abolitionism, to universal suffrage, access to education, race relations, medical practice, the history of marriage and family, and the rights of the accused in the criminal justice system, says Thomas Slaughter, the Arthur R. Miller Professor of History and project director of the Seward Family Archive.

Read more

Seward Family Digital Archive project tops $1 million in grant money

Seward Family Digital Archive project tops $1 million in grant moneyStudents and retired volunteers help transcribe the thousands of Seward family letters written in Victorian-era handwriting.

The myth—and memorabilia—of Seward’s Folly

The myth—and memorabilia—of Seward’s FollyTake a visual tour of just some of the items in the William Seward collection at Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation.

“My Dear Henry…”

“My Dear Henry…”Generations join forces to bring a digital archive of Victorian-era letters to life.