My immediate family and I are no strangers to war. We have lived through several conflicts and numerous civil-war-like skirmishes in the Middle East. Still, we are shocked and almost broken by this one. It's louder, more violent, and more meaningless; and the level of horror we are experiencing in our village and witnessing in cities and towns like Mariupol, Kharkiv, Chernihiv, Bucha, and others is so much greater. The longer this drags on, the more people will die, and those who remain alive will grow angrier and more vengeful. My struggle in this war is about keeping my humanity, even my sanity, and writing this diary is part of that effort.

When looking at the illustrations published here, I was very critical of the quality of my work. I told myself that if it wasn’t for the war and the emotional pressure, I would have produced something better, cleaner. But looking at them now, I realise they reflect what I am feeling. The photos are from places in Ukraine that I visited during the past several years. A lot of these places have now been bombed or shelled. The drawings done over the photographs represent the new reality that didn’t exist when these photos were taken. I dream that one day I will visit these spots again without fearing bombs, forced deportation to Russia, or death.

How I witnessed the war begin

24 February 2022

Caption: How I witnessed the war begin.

I sit at 3am in front of my multi-screen computer set-up, watching several live feeds: a camera near Kharkiv; a broadcast from inside Kyiv; and a couple of news channels. The days leading up to the war have been stressful. Being a news junkie, I've been following the build-up in minute detail, checking every video of military equipment and personnel being moved around us, looking at the maps showing troop positioning.

At approximately 4am, Vladimir Putin goes live. He rants and raves, and officially declares the start of his horrible war. On another feed, I watch a huge explosion in Kharkiv: The sky lights up in a mushroom of smoke and fire. On yet another, I see huge fireballs in the sky over Kyiv.

This is real. The worst has become reality. I run up the stairs to wake up my grandfather. He's asleep with an iPad next to him blaring some random Ukrainian radio station. “Wake up, call uncle, Kyiv is being missiled,” I tell him as quietly and calmly as possible, trying not to scare him too much.

First days of the war in Ukraine

27 February

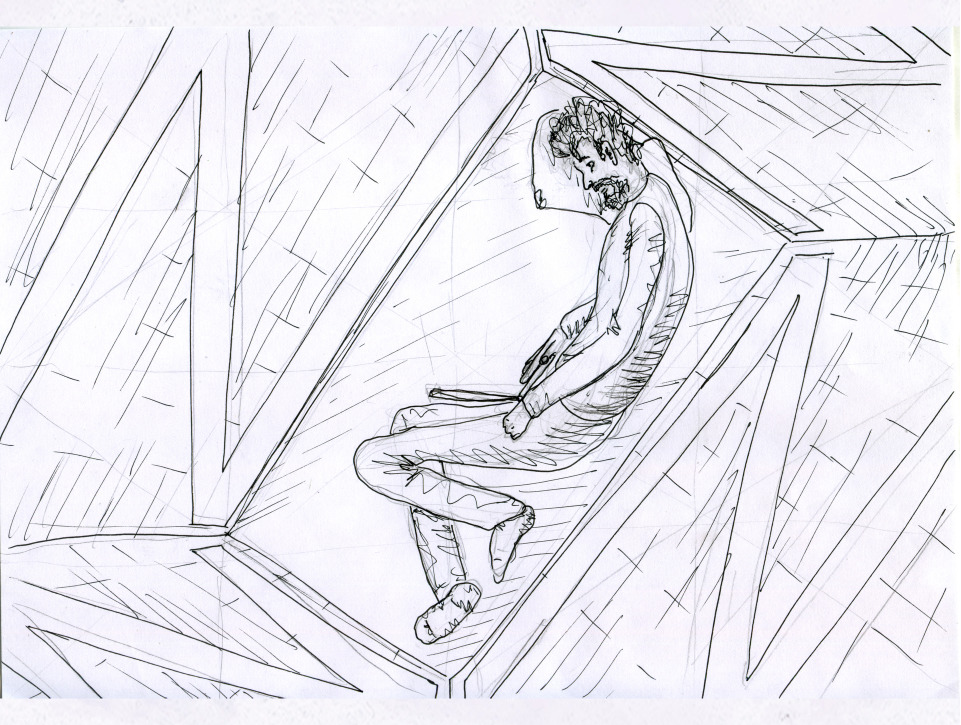

Caption: My family sheltering in the basement as shells fall outside.

I feel like I am about to completely collapse: Totally disheartened, in despair, I cannot eat or sleep. I feel weak and can't force myself to do any work. But work has to be done – a lot of it. My uncle and his family are now here. They were able to escape Kyiv. The entire household is turned upside down in preparation for the worst.

It's beautiful and sunny. The first hint of Ukrainian spring is in the air – warm sun kissing the surface of your skin; earth that will soon be ready to bloom is starting to breathe. I'm working on scraping and painting a metallic frame that will be an improvised bed for the makeshift bomb shelter in the cellar. It almost feels normal. My baby cousin is riding in his toy car going vroom vroom, and then, out in the distance: booooooooooom.

My grandfather, who is almost deaf, does not hear or notice most of the explosions and gunfights in the background. He urges us to keep working, saying it'll only be dangerous enough to go inside if he can hear the explosion.

The days turn dreary and the bombardments grow closer and more numerous. There is constant smoke and fire in the distance; reports of Russian troops moving in closer and closer; the stomach churning pain of endless doom scrolling. l still can’t comprehend that what I’m seeing on my screen is not far away – a few minutes on a bike. I don’t know what or how to feel.

When will this nightmare end?

Kyiv prepares for war

1 March

Caption: A photo of Kyiv in the distance taken before the war, altered to show our new reality.

The days have fused into each other. It all feels like a big lump of undifferentiated time – our new life after this hell has been unleashed. However, my resolve has strengthened. Seeing how our brave military is fending off the beast fills me with strength. I've regained the ability to eat and sleep. I start focusing more on doing what I can.

I knew the electricity and internet connection would be lost soon, so I started trying to upload the huge archive of projects I’ve been working on for the last several years. These aren’t only my projects, but the love and labour of tens of experts from different fields. Friends help me find a large enough storage space in the Cloud, but in the end I barely get a sliver of what I need uploaded because the internet and electricity fail.

Preparations across the house are almost complete: All the windows have been taped to reduce glass shards in case of breakage; old smelly carpets and drapes are hung on every window to stop light from seeping out. We reinforce the basement windows with pieces of sheet metal and wood. All the lights in the house are changed to low energy bulbs.

Russian tanks and Ukrainian resistance

3 March

Caption: What I see when I close my eyes.

Our area is almost overrun. Tens, if not hundreds, of Russian tanks and vehicles are roaming around. The stiff Ukrainian resistance in the rest of the country has almost halted the Russian war machine. The enemy has failed to take even a single large, important city. But around us, there are constant battles. Somewhere not far from me something is constantly shooting. We hear explosions day and night.

Working outside is scary. When the explosions are close, we run to the basement to hide. Before the war, we didn't even lock our doors and cars, and here I am sitting outside with a big bucket full of keys trying to find the right one to lock the backdoor and garages.

Fleeing Kyiv

6 March

Caption: A photo illustration of the one open road leading out of our village.

Spending the past 10 or so days with my uncle's family has been warm despite the horrors outside. I've grown closer to my uncle’s three-year-old son, who's the happiness and joy of everyone around. He makes us laugh and forget about how bad things are. But my uncle, who left Kyiv with his family, is totally lost. Unlike us, they are not half-Arab and have never witnessed war before. They never imagined this to be possible and don't know what to do.

The grim news coming from neighbouring villages gets too much for them. My uncle decides to leave. The roads out of the village are almost all cut, Russians are shooting at cars that try to pass through, with no regard for civilians. There's one remaining way out, along a dirt path that only a 4x4 can cross. My grandfather plans a route using his knowledge from adventuring across Ukraine in his youth. GPS navigation is almost useless here, so they rely on oldschool paper maps.

The night before my uncle and his family left was particularly troubling. I could barely sleep. I was very worried about the family splitting up. The car could only fit my uncle, his family, and my grandfather. I didn't want my grandfather to leave. He is the elder of the family; he built the house we are in, and knows its ways and secrets. If anything went wrong, it would be difficult to fix without his know-how.

But it made more sense for him to leave with my uncle’s family. I was worried about the road ahead of them. I was worried about being abandoned and left behind, but in the end my immediate family and I chose to stay.

‘Russians have started taking people hostage’

7 March

Caption: New walls.

Here we are in a village surrounded by an invading army that is killing civilians and looting. We grow closer and develop better relationships with our neighbours. Our house is one of the few in the village with electricity because we have solar panels. Our neighbours ask us to charge their phones and, in return, despite our protests, they give us eggs, milk, and dairy products. The days are cloudy, and the solar panels are barely getting enough charge. But we are blessed: We still have running water and enough electricity to keep the fridge cold.

There is more and more grim news from the villages and areas around us, which we read online or hear through word of mouth: The Russians have started taking people hostage; they put tanks in their driveways or yards; people aren’t allowed to leave their property; some hide in cellars or sheds.

One of our relatives in the neighbouring village barely escaped with his family. The Russians shot at them as they fled. We hear about people being killed simply for stepping outside. It seems Russian soldiers now have orders to shoot and kill civilians. I don't know if my loved ones and I will make it out of this alive, but an onslaught so unfair and unjust cannot ever prevail.

Fighter jets, burning chemicals, and faith

11 March

Caption: In the eye of the storm as fighting closes in.

Several days have passed since my relatives left. There’s still a slight feeling of abandonment, but I'm happy they’re safe and sound in western Ukraine for now. Meanwhile, our village is being attacked. It's the fifth consecutive day, and the Russians are trying to push through to encircle Kyiv. We can hear heavy combat: the exchange of gunfire, large calibre automatic weapons, artillery. It’s non-stop. Large smoke plumes go on for miles. The smell of burning chemicals and gunpowder is in the air. After dark, the sky is red with fire. Explosions reverberate more violently in the quietness of the night.

The sound of jet planes roars by. Minutes later, there’s a news report that a neighbouring city was bombed hard. Was it those planes? I still feel “safe”, although the fighting is only a few hundred metres away from where my family and I are. I still have hope. I believe we will triumph. This assumption might be wrong, but I have faith in it. It is propelled by some logical things, but mainly it's just that – faith.

Medical supplies and household comforts

12 March

Caption: Almost looks normal on the outside.

The first few days of the war, waking up was very painful. For that millisecond before reality set in, I was still okay. Then, it would fall on me like a tonne of bricks: I wasn’t waking up from a nightmare – I was waking up into one.

Now, waking up is a bit easier. I’ve grown used to the sounds of explosions outside, and I keep telling myself, ‘those are our guys shelling, so I’m safe’. I have no way of knowing this for sure, but thinking it makes me feel better.

I sit with my mother and younger brother at the kitchen table discussing the news and our situation while I drink a warm cup of chocolate milk. Coffee, tea, and almost all other household comforts – even basic necessities – are in very short supply. Medical supplies are even worse. Even feminine hygiene products are in short supply. People send requests and coordinate with each other on messaging apps to try to provide for people’s needs, and the local administration helps where it can.

Each day I thank the gods we have running water. I remember how difficult it was in one of the cities where I lived in the Middle East during wars or airstrikes when water was strictly rationed. In Ukraine, our village has old fashioned hand-cranked wells, and unless the Russians poison them, we are in no danger of dying from dehydration – a fate many are facing in besieged cities such as Mariupol.

I go outside and give some love to my dog, who’s doing remarkably well, braving this whole thing. I feed him only once a day now. His food is running super low. I think tomorrow it will be finished, and we will have to improvise to feed him.

‘We are the front line now’

14 March

Caption: A photo illustration of the missile that exploded above our house.

I miss my three-year-old kid cousin. He used to be afraid of me before the war because I was never home and lived in Kyiv. He was too young to understand what was happening. “Bakh” [boom]? He would ask. “Bakh,” we told him, nodding. He didn’t mind the explosions and kept twirling around in the basement, laughing and enjoying all of the attention we were giving him. Now, he is far away in western Ukraine, safe – at least for now.

I had a conversation with a neighbour who is in the know about the situation around us. “We are the front line now, aren’t we?” I asked. “We are,” he replied. “There are so many Russians around us, you can’t even imagine.”

The fighting feels louder and angrier. Shells fly overhead more often. A large missile explodes right above us. Wreckage rains from the sky and lands on our neighbour’s property across the road. Thankfully, it’s just debris – nothing explosive – and only damages the roof of their barn.

At 10:17pm, I go outside. There’s an eerie sound – a deep, deep, bassy growl, as if the earth was an angry monster. I can’t tell what it is. It could be tank engines, or it could be something else. But it doesn’t stop. It’s a solid, constant layer of sound in the background. Every now and then, the sounds of huge explosions can be heard on top of it. The air looks like it’s on fire.

I wake up the next day with that sound still in my head. I will never forget it. To me, it’s what the apocalypse sounds like.

The war is everywhere

15 March

Caption: The war is everywhere.

I’m in the garden shovelling soil when I recall one of the darker videos I’ve seen during this war: A Ukrainian farmer takes the corpse of a Russian soldier away; the implication is horrid – he’s going to use it as fertiliser.

I hate what this war has done to me. In the past, whenever I observed wars and conflicts, I always felt sorry for the people in them – the innocent ones dying for no reason and the armed ones fighting each other for little to no reason. I felt sorry that those people were in that situation, regardless of whether I thought they were fighting on the right side or wrong side. I wanted to hope that they were just people who had been deluded, but that they had been good at some point and still had good in them.

But no more. I look at the bodies of dead Russian soldiers, and I feel nothing. These people are here to kill me, and I'm glad they’re dead. I listen to the intercepted phone calls. There are hundreds of them, intercepted by Ukrainian intelligence. They are posted on YouTube and other platforms. They feel too authentic to be fake, and they make me hate even more: Russian soldiers bragging to their mothers or romantic partners about how they stole them a nice mink coat or a 500 watt blender. It’s like they are real 21st century barbarians.

I’m digging in the soil while having these thoughts because we must grow food. Whatever the outcome of this war, one thing is certain: Food is going to be a problem and in short supply, everywhere. We must plant every seed and sapling we can find. No one knows what is going to come next.

How to live under siege

16 March

Caption: Mundane household items given a new purpose.

- Put tape on windows, in the pattern of X or Ж, to reduce shattering in case of a close explosion; Build a contraption to hold old rugs and carpets in front of all the windows to block glass shrapnel; Add opaque layers of tarp or material to stop any light emitting to the outside.

- Find keys to backdoors and sheds to lock doors no one has locked in years; Move everyone’s sleeping area to the first floor because the second floor is too dangerous; Clean up the dusty basement and remodel it into a shelter; Bring board games, playing cards, lego blocks, and pens and paper to the basement to have something to do during long hours in the shelter.

- Put an old bathtub outside in the yard and fill it with water in case of fire; Always keep a flashlight handy; Get used to the sound of artillery constantly exploding and firing around; Learn to differentiate between the sounds of different munitions and how to keep track of the movement of friendly and enemy troops.

- Worry about electricity, internet, and food and medical supplies; Hope dog food somehow becomes available again; Become irrationally happy when you manage to find some.

- Realise that the smog of war is a real thing: Unlike the fog of war, which is an abstract idea, the smog of war is the thick dirty film that hangs in the lower atmosphere for several days after a battle; It smells like burnt chemicals and garbage.

- Learn how to wake up again without having the world crash down on you all at once in that first gasp of consciousness; Remember your faith, and try to have more faith; Speak to friends and family you haven’t talked to in ages; Draw your horror; Disassemble and stow away your expensive computer system; After a while, take it out and set it back up.

- Dare to dream again.

Survivor's guilt

19 March

Caption: Who will look back at me from the mirror?

As spring draws closer and closer, the days become more beautiful. I feel guilty finding a lapse in the horror to enjoy that beauty. I feel guilty for having clean running water while people out there are under bombardment, melting snow to drink. I feel guilty that I can sit at home, warm and relatively safe, and put on a video to drown out the sounds of explosions outside while some people are sleeping in cold, dark, damp cellars while the end of the world shakes the walls. I feel guilty that I have internet to see how the front line is shifting: Today, it’s 12 kilometres away; two days ago, it was two kilometres away; four days ago, it was 200 metres away, on our main street. Somewhere the front line is on top of someone’s head.

I don’t know if I will live long enough to read these words again and reflect on them, but I write what I am feeling. I still have faith. I still have hope. By staying alive and continuing our existence here, we are fighting.

A little while after writing this our village took a direct hit. Several very large explosions shook the whole area, and a very large fire erupted. The local administration warned everyone not to post pictures of the strike on social media, otherwise “we would be f****d!”, they said. Posting pictures of the areas that are hit helps those firing to adjust their aim. After living through this strike, the lingering feeling of guilt is mostly gone.

War threatens to strike

20 March

Caption: The ever-accelerating pendulum of war threatens to strike, erasing normal life in its path.

I remember the early days of the war, which now feel like a lifetime ago. I remember how each explosion would send us running to the basement. Now, we barely react.

Early on, a large cruise missile hit an oil depot that was relatively far away. The explosion was huge and the air all around us looked like it was on fire. Our whole family ran around picking up random supplies to bring to the shelter. It took us about 10 minutes to collect everything we thought we needed. By that time, we realised the fire was quite far away. Reflecting on it, if we had really been in danger, the way we acted would not have kept us safe.

Another time, before Russian troops were in our area, a fire started in a field next to our house. No one knows how it started, but it could have been Russian saboteurs. I ran to put out the fire. When I came back, I sat at my computer with char-covered hands and typed on my new keyboard, which I bought only a couple weeks before the war started. I could have washed my hands, but didn’t, and I didn’t know how to feel as my dirty fingers ruined the pristine keys. Did I really care? Did it really matter in the context of the nightmare that was gathering force around me?

Days later, after I had packed up and put away my computer for safekeeping, I regained my composure and started gaining faith in how things were going. I took my computer out and cleaned the keyboard. I can’t really explain why this trivial detail mattered to me and why I chose to write it down, but it did.

Neighbour’s house hit by shelling

22 March

Caption: Photo illustration of our neighbour’s house that was hit by shelling.

7am. I wake up to the sound of loud explosions. “BASEMENT!!!” I yell at the top of my lungs. We rush down to the basement. The barrage lasts for a good five minutes. When the bombardment stops and I go upstairs, the neighbour’s house is on fire. It must have taken a direct hit.

Why? Why are they bombing a small civilian house in the middle of nowhere? Why did they hit our neighbour and not us? Our house is bigger and a clearer target. God, I hope no one got hurt. I am still too shaken while writing this, but I had to jot down a few words.

4pm. I’m sitting at my desk sipping a fresh cup of birch juice tapped from the white birch tree in our yard. Reflecting on this morning, I realise that the horror just increased a level where I am. There is still no word about whether anyone next door was hurt. My nerves are still holding, but I don’t know how much it would take to break me. If we make it out alive, I hope we will still have our mental health.

Will we ever fully recover?

27 March

Caption: A photo of Crimea before it was occupied in 2014, and an illustration of me dreaming of freedom.

Explosions grow thicker. Troops become more numerous. Yet, my faith grows stronger every day, even though it is intermixed with dread.

Before the war, I lived in many places – in the Middle East, Europe and, for the last several years, Ukraine. What I felt was unique about Ukrainian people is how smart and talented they can be. In Soviet times, Ukraine was one of the main centres of science and technical development. Ukrainian artists and creatives always awed me. I lived and dreamed in this rich environment before this nightmare came to us.

I hope we survive this. I hope the beautiful, peaceful, happy world I once knew will come back, after we are able to heal. I want to listen to music again, to laugh, to love, to be able to not think of the horror and chaos we are living through right now. Will we ever fully recover?

Ukraine was never a perfect country – if such a thing could exist – but I loved it more because of that. Everything seemed possible with enough effort and luck: startups, media projects, art projects, adventures, photography, beauty, life, love. That is the kind of world I now realise I have lost – but not forever.

Edited by Eric Reidy.