Jennifer Straughan struggled with her weight for decades. By her mid-forties she had tried everything: diets, journaling her food intake, exercising constantly. “It controlled my life,” she says. “I would obsessively work out. I’d get up in the middle of the night if I forgot to enter something I’d eaten into my tracking app.” Worst of all, looking good was more than a vanity project. Straughan is a fitness instructor. At five-foot-three and hovering around 175 pounds, she found her clients becoming skeptical.

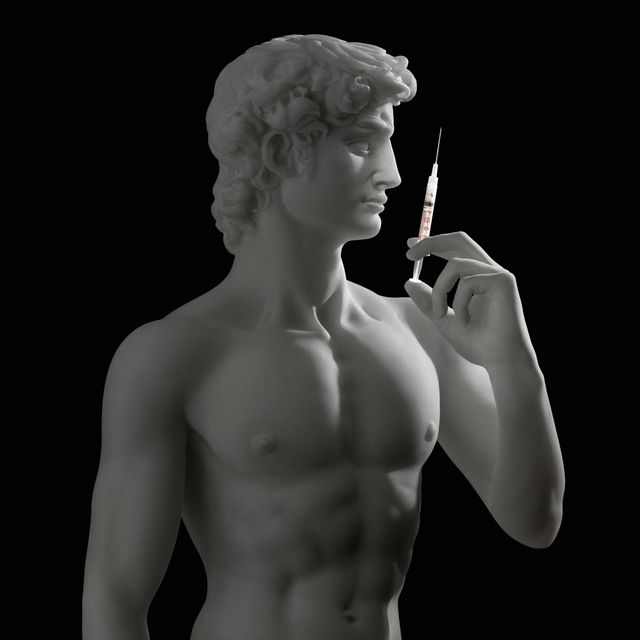

About four years ago Straughan went for a regular checkup in her hometown of Toronto to a doctor who specialized in weight loss, and her stress all came pouring out. “For some reason, at that moment I just lost it and blurted out everything I’d struggled with for 20 years—the addictiveness of it. And he said I was a good candidate to try Ozempic.” Now she’s down to 130 pounds. If you spend enough time at the right dinner parties or on TikTok (search #MyOzempicJourney), you’ll eventually hear about Ozempic. It’s a brand name for semaglutide, an injectable insulin-regulating drug developed by Danish pharmaceutical giant Novo Nordisk to treat diabetes. When doctors began noticing that their Ozempic patients were losing weight, the manufacturer conducted clinical trials on overweight and obese people and found that using the drug did indeed lead to significant weight loss. Alongside its insulin promoting effects, semaglutide slows down digestion, so patients feel full for longer after eating. Novo Nordisk also started marketing a higher-dose treatment of semaglutide for obesity, calling it Wegovy.

But now people who are neither diabetic nor obese are turning to the low-dose formulation as a quick and simple way to lose weight. One woman in a tony New York suburb tells of another woman who underwent “a total transformation” over a year. “It was the talk of the town. We were all marveling that she was wasting away—we meant this as a compliment, of course,” she says, not facetiously. Then the same thing happened to the wisp’s best friend. “Ultimately I heard they were both on this drug called Ozempic, and I told the story to a friend. And my friend says, ‘Of course. Everyone’s on it!’ ”

“If you’re more than 20 pounds above your ideal BMI, then you can find doctors who will write you this prescription,” says Nancy Simpkins, a prominent New Jersey–based internist and government medical consultant who does not personally prescribe Ozempic for weight loss but knows several well-respected colleagues who do. “It just regulates the glucose/insulin metabolism, but you have to be able to tolerate the side effects.” She’s referring to the gastro intestinal phenomena—bloating, constipation, diarrhea—that unfortunately accompany these drugs, as well as metformin and others that are oral forms of insulin regulators. Clearly, though, many patients have decided the stomach upset that comes with their weekly at-home injections is worth it.

Using Ozempic purely for weight loss is called “off-label.” Once a drug has been established as safe by the FDA, doctors can technically prescribe it for any indication they like. But that doesn’t mean it’s necessarily a good idea. “We cannot and will not promote, suggest, or encourage off-label use of our medicines,” says Natalia Salomao, a senior director in Novo Nordisk’s U.S. office. In addition, off-label use isn’t covered by insurance, which means that finding a doctor willing to prescribe Ozempic to help you shed your extra pounds is only one of the hurdles. “Not everyone can do this,” Simpkins says, “because it’s close to $1,000 a month out of pocket. But people with resources increasingly want to jump right to these injectables.”

“It’s the typical American way: Let’s take a drug to take care of my problem,” says Stephen C. Brewer, medical director at the famed wellness resort Canyon Ranch, outside Tucson. “A patient told me yesterday he’s on Ozempic: ‘My doctor gave it to me to lose those extra pounds.’ ” Brewer says he will consider prescribing semaglutide only as a last resort. “Trying to scrape off the last few pounds that way? I’m not in favor of that at all.”

Both Brewer and Katie Rickel, a clinical psychologist and CEO of Structure House, a weight loss management clinic and retreat in Durham, North Carolina, say that weight loss and weight management are about lifestyle—not just diet and exercise but sleep and stress management, too. “Making someone less physically hungry is not going to solve the whole problem,” Rickel says. “People misuse ADHD meds and even cocaine for weight management purposes. Sure, doing coke might help you lose a few pounds, but weight management is multifactorial—there’s no magic bullet.”

Yet gossip mills and social media are rife with newly svelte fans. “My cousin was always a little chubby,” says another woman from a prominent family. “And she tried every trendy diet and workout: F-Factor, you name it. Then recently she starts posting pictures of herself on Instagram looking incredible in these supersexy midriff-baring outfits. And what do you know—she’s on Ozempic.”

Simpkins remembers older generations of weight loss drugs like Fen-Phen, which were all the rage early in her career. “Doctors were essentially using legal speed off- label to help patients lose weight, and some of them died of heart attacks,” she says. She’s more optimistic about this new generation of drugs, although she emphasizes the importance of expert oversight of any off-label use. “You need to see someone who knows what they’re doing and isn’t just making a business out of demanding patients wanting to be skinny.”

This story appears in the September 2022 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

Paul Tullis has covered science, technology, and other topics for The New York Times Magazine, Scientific American, Nature, Bloomberg Businessweek, Slate, and many others. His work has won awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, Society of Environmental Journalists, Association of Food Journalists, and others. Born in Chicago, he now lives in Amsterdam with his wife and two daughters.