The history professor leads his class back in time to analyze events that shaped today’s world.

Pablo Sierra Silva’s teaching philosophy is driven by two words: primary sources.

“It’s the foundation of any historical work,” according to the associate professor in the Department of History at the University of Rochester, who is one of this year’s recipients for the Goergen Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching. “A decree, a quote, a petition from long ago—how we interpret the primary source will always change depending on who is interpreting it, and when.”

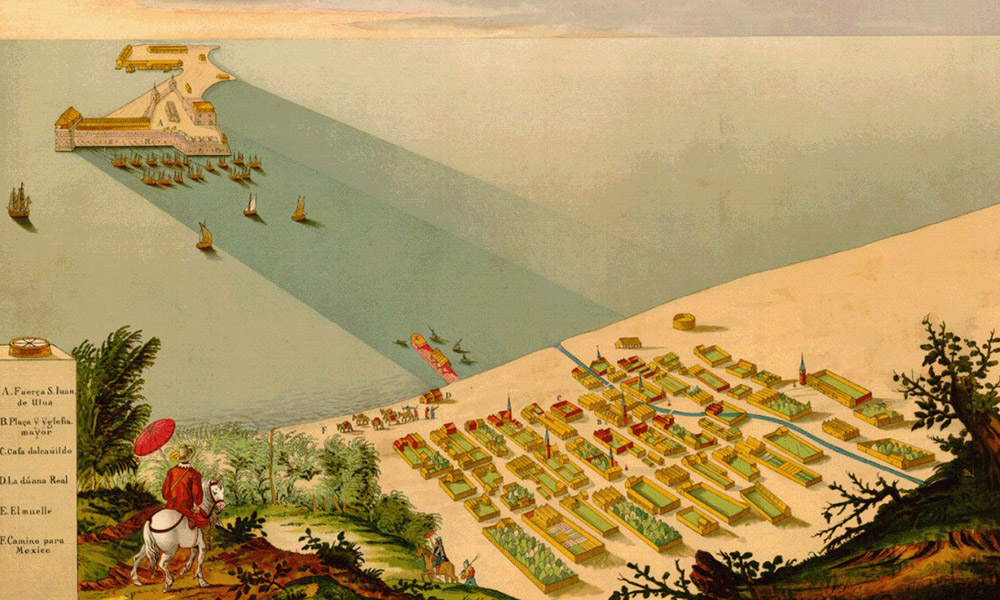

Sierra Silva’s research centers on the experiences of Africans and their descendants in colonial Mexico, the Caribbean, and the Atlantic during the 16th through 18th centuries. His immersive teaching style allows students to put themselves in the time and place of the people they’re studying.

“I make them active participants in a given historical moment,” he says.

In one example, his class was reading a petition from Spanish nobles to their monarch, requesting privileges and rights they wanted recognized. “I asked my class to consider this petition from both sides, but to also imagine the parts that weren’t drafted, the letter that wasn’t sent,” Sierra Silva says. “When you start to imagine these possibilities, then history really becomes immersive.”

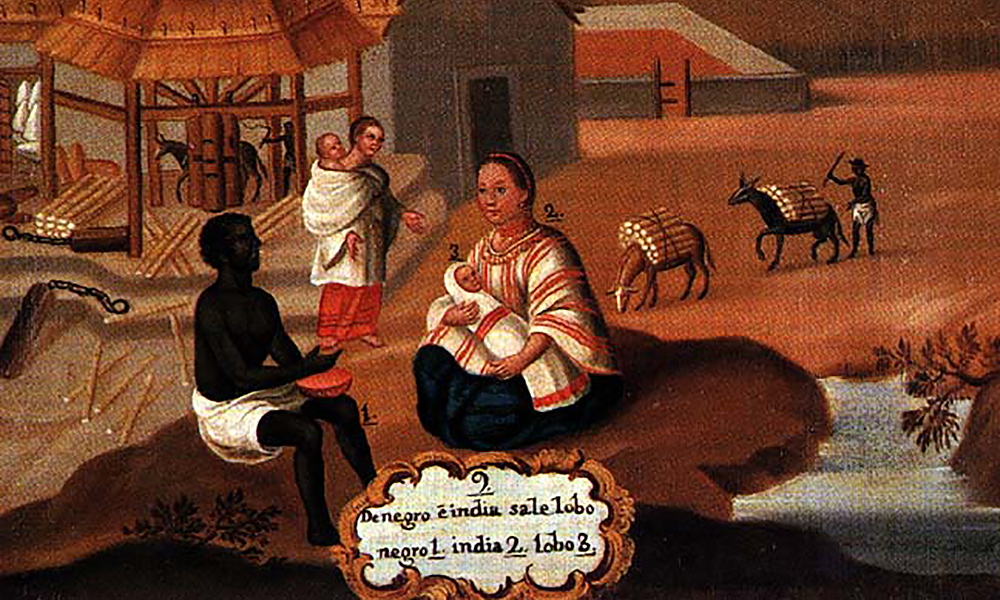

And occasionally even uncomfortable. “Trying to make sense of how a slave trader 500 years ago could justify selling a family, that’s really difficult for students to step into that role,” he says. “So I tell them, ‘No, think of this in terms of a witness in the room when this bill of sale is being written. Be in the moment. The intent is not to recreate the trauma suffered by enslaved people of African, Asian, or Native descent in Mexico, but to have students understand how and why colonizers dehumanized members of their own societies. The next step is to understand how oppressed people overcame or resisted their enslavement.”

Of course, there’s more than one way to bring the past into the present. For Sierra Silva’s seminar course, The Other Atlantic, students learned how to prepare an indigenous Mayan drink made with cacao.