How the largest environmental movement in history was born

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEarth Day emerged from the disquiet that many felt at the destruction of the natural world and has evolved into a global environmental movement. The BBC talks to some of the original and more recent organisers to hear how it has changed.

Ageing protesters still speak of the first Earth Day with reverence. On 22 April 1970, 20 million people took to the streets across the United States to protest environmental destruction. The nation had recently witnessed the devastating impacts of the Santa Barbara oil spill and seen the first photographs of the Earth taken by astronauts. The beauty of that blue marble pictured from space contrasted bleakly with the lamentable state of the Earth that they knew from the ground.

The campaign was led by a senator from Wisconsin called Gaylord Nelson, and organised from a temporary office in Washington DC staffed by college students, many already veterans of protest campaigns of the 1960s, including the civil rights movement. But anyone was free to arrange their own festivities. "That was the remarkable thing about Earth Day," wrote Nelson more than three decades later in his book Beyond Earth Day. "It organised itself."

You might also like:

It may have been the start of the modern environmental movement, but it was not the origin of environmentalism. Scholars have argued that the tenets of environmentalism are found into the Koran, which was written in the 7th Century. And throughout the 20th Century, countless protesters have been killed trying to protect natural environments and animals, with numbers of killings rising rapidly in recent decades.

Getty Images

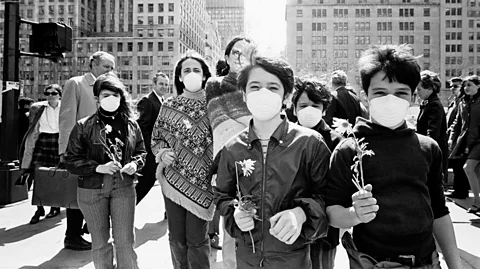

Getty ImagesWhile Earth Day was far from the first environment action, what made the movement different was its mass scale and coherence. The first Earth Day events took place at tens of thousands of locations across the US. Even a stretch of New York's Fifth Avenue was closed to traffic. Congress was adjourned, as so many politicians were participating in the day's events. Earth Day created, for the first time, an environmental movement, as local and specific concerns around clean air, water and pesticides coalesced into a broad awareness of the crisis facing the planet as a whole.

The event was larger many times over than its organisers had anticipated. "Our aspirations were to have an event that resembled some of the anti-war rallies and civil rights rallies. But instead of having them in one or five communities, we looked at it in many cities across the country," says Denis Hayes, who organised the original Earth Day.

"By the time it finally came around, it was in virtually every town, every village, in the United States. It took this basket of issues that we now call 'the environment' and elevated them spectacularly in the public consciousness."

A bumpy road

The more cinematic narrative of Earth Day has it that the movement had politicians in the US jumping over themselves to implement pro-environment legislation. But in fact, the clamour actually quietened down following the festivities. The following week, America invaded Cambodia and the Ohio National Guard shot dead four unarmed college students at a protest at Kent State University, leading to a renewal of anti-war sentiment. But still, something had been stirred, and the Earth Day organisers were not easily put off. In late summer, they waged a campaign against 12 members of Congress with poor environmental records, eventually booting seven of them out of office.

Getty Images

Getty Images"That's when Congress began taking it seriously," recalls Hayes. Suddenly, the environment was a vote-winning – or, in this case, a vote-losing – issue. In December 1970, Congress created the Environmental Protection Agency, and over the next decade it passed a raft of legislation aimed at cleaning up the nation's air, water and other natural resources. The status quo – that of a nation where rivers caught fire and bird numbers were decimated by pesticides – was becoming increasingly unacceptable to many American voters.

CARBON COUNT

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

The 50th anniversary of the first Earth Day looked very different. With the global pandemic changing the way we live across the world, the planned events were scaled back to digital protest. It was a huge change for an event that has grown in the schools and communities of more than 190 countries.

It was another in a long line of transformations; the Earth Day of recent years has been a very different beast to its first iteration in 1970. In the past five decades, the movement has shifted to account for societal changes, technical advances and emerging environmental challenges, of which the most notable is, of course, climate change. Barely on the agenda in the 1970s, the consistent rise in global temperatures is now environmentalists’ overriding concern.

The greenwash question

Earth Day has always faced criticisms, and their nature has shifted over the years too. In his book, Gaylord Nelson comments wryly on the dogged accusations that Earth Day was actually established to honour the 100th anniversary of the birth of the Russian communist leader, Vladimir Lenin. Today, the movement faces regular suggestions that it has lost its original revolutionary fervour, instead prioritising token gestures and a focus on individual action in place of political upheaval.

"The first Earth Day was unrepeatable. It was unprecedented," says Adam Rome, a historian of the environmental movement at the University at Buffalo and the author of the book The Genius of Earth Day. Back then, the organisers were focused on a radical transformation of society, he says, but that attitude shifted around the 1990s. "In most places, in most years, it's either been kind of a trade show, where you can see the latest green goods; or, for kids, it’s a day to plant trees or collect litter. Earth Day itself is not nearly as much about collective action to deal with huge problems as it was in 1970."

The potential for greenwash is a problem with which Earth Day organisers have long grappled. While the movement is spearheaded by the Earth Day Network, companies and brands regularly use the annual celebration as a way to promote their "green" products and services. "I worry about it, but we're incredibly activist about trying to tamp it down. That's our behind-the-scenes game every single year," says Kathleen Rogers, a former lawyer who now leads the Earth Day Network. "But they keep trying to do it. That's just the name of the game."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNelson, who died in 2005, adopted a pragmatic attitude towards any corporate co-opting of the Earth Day brand. He recognised that all the world’s problems cannot be resolved by a celebration that takes place once a year, and that there was a need to engage with business and industry. "Whether a corporation wants to appear green for public recognition, or for perfectly honest reasons, it doesn't matter. The fact is, we're gaining," he wrote in Beyond Earth Day.

This flexibility has perhaps been the key to Earth Day's persistence through its first 50 years. While the official Earth Day Network runs various official initiatives each year, the day’s meaning is reinterpreted differently, hundreds of times over, by the individual events organised by schools, faith groups, cinemas and artists.

This has helped the movement morph itself to fit local social norms and new political regimes – Hawaii, for instance, is hosting a dolphin-themed event this year, while the African network has highlighted the destruction of the Congo Rainforest. Since its American beginnings, Earth Day has reached countries on all continents, including Iran, Nigeria, Argentina and Australia.

Earth Day's leaders see diversification, away from the white middle-class stereotype of environmental activism, as one of the main achievements of the campaign. "In the Middle East and Africa, the environment is not a priority," says Rusul Al Shihab, who began campaigning as a volunteer after arriving in the US in 2009 as a refugee from Iraq, and is now director of Earth Day 2020 for the Middle East. "Ironically, the whole region is affected by climate change. We see floods, we see rain, we see temperature rising."

Youthful beginnings

When Earth Day began in 1970, there was no other protest like it. Today, it is just one branch in an enormous ecosystem of environmental movements, many of which are louder, more political and youth-driven. Jamie Margolin, who founded the youth movement Zero Hour from her home in Seattle, says that she started to appreciate Earth Day when she learned about its revolutionary roots, and now believes that it is a useful tool in bringing people together to tackle environmental problems, whatever their backgrounds.

Getty Images

Getty Images"Initially, I was not a big fan, because it seemed to infantilise the problem. I didn’t know the history; I just saw in schools they would put up signs about saving the trees," she says. "But different communities need different things when it comes to solving the climate crisis. If you have a holiday that allows each community to commemorate it in a way that best fits their needs, I think that’s a good thing."

It is youth movements like Zero Hour, alongside the school strikes spearheaded by Greta Thunberg, that are leading the climate movement today. But it's worth remembering that Earth Day, when it started 50 years ago, was also led by young people: fiery students who had witnessed the decline of the natural world and felt as impassioned to solve it as many feel about climate change today.

So the story has come full circle. When Margolin set up Zero Hour, she was guided by insights from another local Seattleite: the original Earth Day organiser, Denis Hayes, himself. While the movement may not be the radical force it once was, it was arguably the seed for the modern ecosystem of environmentalism that is alive today.

* This article was originally published on 22 April 2020.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.