You take your three children to McDonald’s, not expecting to fight with Jessica, your 10-year-old, but she throws herself onto the sticky floor, screaming because you put ketchup on her fries. When you finally convince her to take your set of untouched ones, she sits down, then gingerly plucks at the pile while eyeing you with a look of distrust. She lifts one golden fry and studies it like a specimen before she pops it in her mouth. Your other two children are pulling toys out of their Happy Meals, unfazed by their sister’s meltdown. They are used to this. You ask yourself if you should have gone through the drive-thru.

The din inside the McDonald’s annoys you. You observe families seated in the shiny red booths, deftly unpacking bags, crumpling paper, all enjoying a normal, everyday outing. A heavy-set woman approaches your table. You hope that she is coming to offer praise for the way you handled the chaos, but when you glance at her face, you see the scowl. She points a finger, her voice rising as she demands, “Why don’t you control your child? What kind of parent allows her kid to behave like that?”

You refuse to look at her and instead stare at the splotch of yellow mustard on the edge of her canvas sneakers. Everyone must be watching you — you, the mother who can’t control her child. The woman finally stops her rant, flicks you the finger, then stomps off. Only then will you dare to look around.

You notice the family across from you, the mother busy helping her child tear open a tiny packet. No one is watching now, but you feel certain everyone in McDonald’s thinks you’re a terrible parent. You want to fade into the red plastic seat.

Your 12-year-old daughter, Alia, is indignant. She pounds on the table and says, “Mommy, that lady can’t talk to you like that. Why didn’t you tell her?”

At first you will not understand what she means. Then you remember. Alia is talking about the family therapist, the one who suggested you tell your other children their sister had a “broken brain.” You recall how much you hated that label because it didn’t describe Jessica. She wasn’t broken. Yet you parroted the doctor’s words. Now you blame yourself for never thinking of an alternative. Maybe you thought it was true.

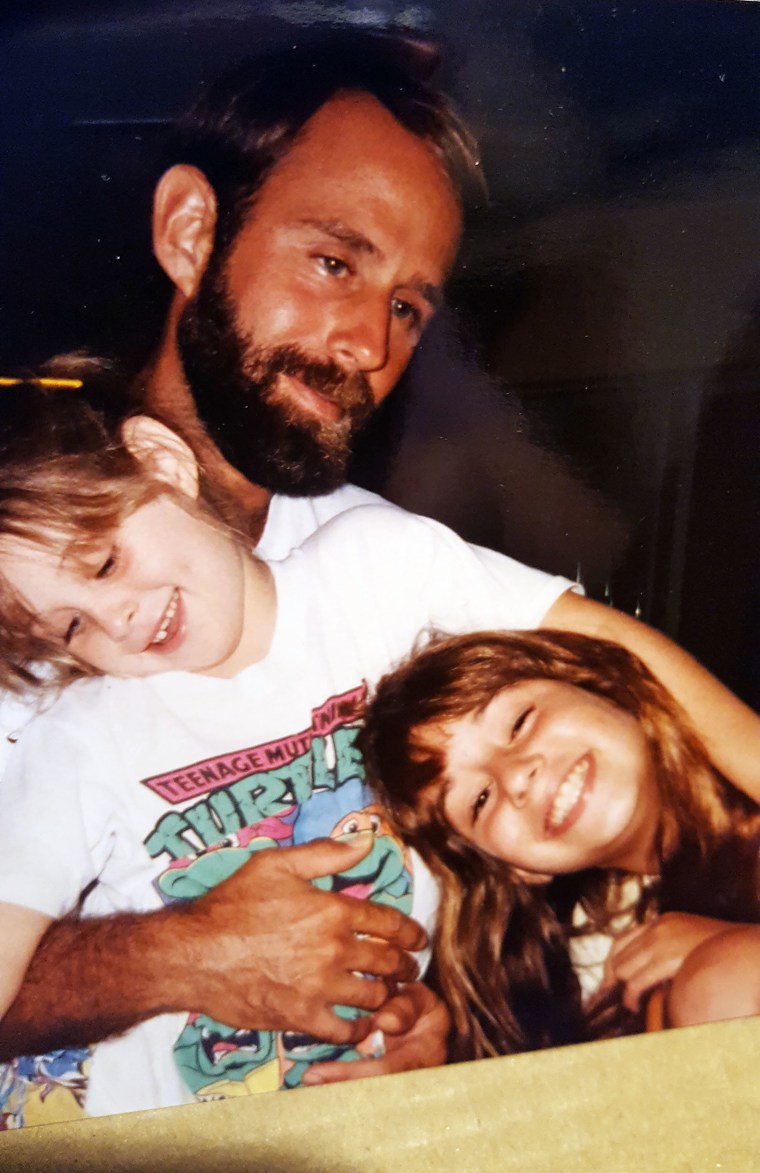

Alia asks if she can go play. You nod and tell her yes, if she takes both her sisters with her. Jessica and Sarah follow Alia to the play area. The girls will not be aware of the way the perceived attack has shaken you. This is not the first time you have been confronted about your parenting. In the future, you will face similar situations again and again. Your mind will replay this moment. You think of the pediatric neurologist, the one who casually pronounced your daughter “profoundly retarded.” You long to go back and erase everything.

Many years later, Alia, Sarah, their husbands and their four children stand in your living room to celebrate Sarah’s birthday. Alia, the family party planner, sent out the invitations and arranged the catering. The guests will mingle around the buffet, drinks in hand. You overhear someone ask Sarah, “Isn’t it Jessica’s birthday too?”

Jessica will be glued to your side, reluctant to greet strangers. Every time someone approaches, she lowers her chin and grasps the hem of your shirt. You remind Jessica about her birthday celebration the previous weekend — dinner at the restaurant, the family and friends, the presents. Jessica smiles her lopsided grin and asks, “When we go again?”

Now you regret you didn’t leave Jessica at the group home. But this is Saturday. And Jessica comes home on Saturdays. For a moment, you consider taking her back, but it’s almost time for her to go to bed.

You hand Jessica a bowl of popcorn and tell her you want her to watch TV in her room. She lumbers down the hall, and for the millionth time, you must remind yourself to be grateful for her accomplishments. Your mental checklist recounts these things: She can make something for breakfast that doesn’t require cooking and doesn’t spill the box of cereal all over the floor. She can choose her clothes and dress herself and navigate most of the apps on her iPad. Although your 30-year old daughter manages most of her personal hygiene, she still needs help rinsing shampoo out of her hair.

You follow Jessica into the darkening bedroom and as you flip on the light, you notice the unmade bed. The sight of it makes you want to lie down, but you can’t because there are 50 guests in your living room. Jessica needs a shower before she goes to sleep. When you tell her this, she will say, “Get out, I big girl. I do it.”

You decide she doesn’t need to wash her hair tonight.

What you resent more than anything is the way you see yourself. The bedraggled mother of a child with a disability.

Within 15 minutes, Jessica is fast asleep, but the caretaking has tested your patience. What you resent more than anything is the way you see yourself. The bedraggled mother of a child with a disability.

A failure.

You will think of your own mother, a woman who criticized you for being different, for wearing jeans and riding your bike around the block with the boys instead of wearing dresses and playing with dolls, and you chastise yourself for all the ways you have criticized Jessica’s differences. Your inner voice says, “I failed. I am just like my mother,” even though it’s not true.

When you return to the party, someone you don’t know hands you a drink. She tells you she’s friends with Sarah, and says, “Sarah told me Jessica is her twin. They don’t even look alike. I didn’t know she has special needs. She doesn’t look handicapped.”

You will smile and maybe nod, but you won’t know how to respond. You have never understood the empty platitudes. You wonder if Sarah’s friend implied that being handicapped was inherently tragic.

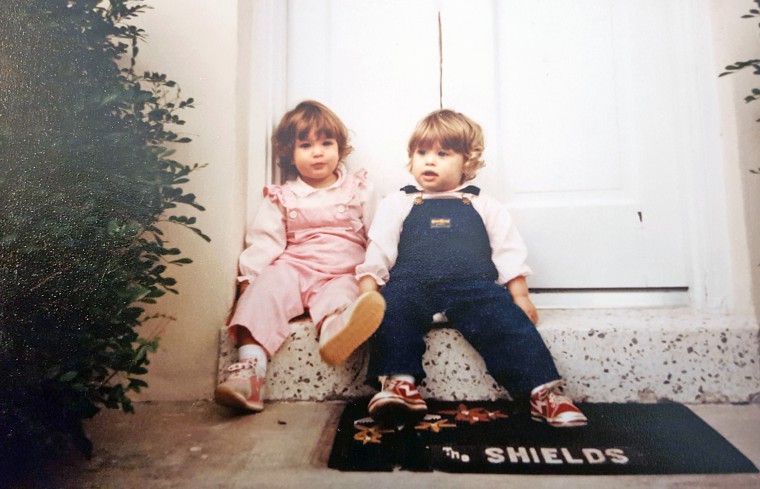

Sarah’s husband is snapping pictures. Sarah’s 6-year-old daughter, Lexi, runs over to show you a photo of Aunt Alia and her mom, Sarah. In the photo, you notice how your daughters have their arms wrapped around each other, manes of golden hair cascading around their shoulders.

Lexi points at the photo and says, “Grammy, you have two pretty kids.”

Her comment catches you off guard. Lexi asks you what’s wrong, so you must have stopped smiling. “It’s nothing,” you say.

But it’s not nothing. You put on the best matter-of-fact face you can muster. This is your moment of clarity. You can finally address what you have always been afraid to face: your secret shame.

This is your moment of clarity. You can finally address what you have always been afraid to face: your secret shame.

Lexi doesn’t know her statement triggered memories. You not only recall the incident in McDonald’s, but you think of the hundreds of times you didn’t speak out. You suddenly feel empowered. You say, “Lexi, let’s sit over there so I can share something about your Aunt Jessica. Maybe you have questions.”

Lexi nods. She looks at you expectantly as you say, “I have three pretty daughters.” Then you pause for effect before adding, “Aunt Jessica is one of them, just like your mom and your aunt Alia.”

Lexi twists a strand of hair in her fingers. The expression on her face tells you she thinks you’re mad. She asks if you are.

You reassure her, then explain why Jessica is different. You talk about a person’s uniqueness. You say, “Lexi, Aunt Jessica likes to watch the same cartoons as you and she has curly hair and blue eyes, just like you. But your brother is different. He doesn’t like cartoons. He watches the sports channels and has straight hair and brown eyes.”

Lexi wants to know why Aunt Jessica can’t read or write or drive a car. You struggle for the right words, and somehow, you find them.

“Aunt Jessica can do some of the stuff you do but she had something happen to her brain when she was born. That’s the reason she has so many limitations.”

There is a call to cut the cake. As you follow everyone to the table, you wonder if your talk made any difference. You remember your own lifelong struggle with acceptance but feel proud of what you’ve done to help Jessica.

Today marks a new beginning. You are changing the narrative.

Do you have a personal essay to share with TODAY? Please send your ideas to TODAYEssays@nbcuni.com.