| Author: | Sören Schneider |

| Date: | 11. August 2023 |

Anticipatory humanitarian action (AA) seeks to leverage information on the occurrence and impact of disruptive events, such as extreme weather events, to anticipate and minimise their humanitarian consequences before they fully materialise. Although anticipatory action is gaining traction within the humanitarian system, the broad range of smaller and medium-sized NGOs is still facing major barriers to the successful adaptation and implementation of the approach. This blogpost seeks to discuss the particular challenges associated with trigger development, that is the complex process of identifying thresholds for early action based on available forecast- and impact data, as one of these barriers to engage in anticipatory action. It argues for more flexible approaches to anticipatory action, in which local knowledge and partnerships can be key entry points to facilitate trigger development. To do so, however, sustained efforts to reconcile the paradigm shift towards a more anticipatory way of working on the one hand and the international localisation agenda on the other hand will be necessary. The findings and recommendations of this blogpost are derived from bilateral exchange and discussions with several NGOs that are already engaging or aspire to engage in anticipatory action. Additionally, the semi-systematic analysis of evaluations and recommendations from a six-part training program on anticipatory action was used. Beyond this, an exchange workshop on anticipatory action among German NGOs in October 2022 and participation in other exchange fora as well as relevant literature were included.

Scaling up anticipatory action: the status-quo and current challenges

Anticipatory action aims at protecting lives and livelihoods by acting before a disaster strikes. To achieve this, pre-agreed thresholds of hazard variables like windspeed or river levels, that indicate a certain extreme event requiring humanitarian action is likely to happen (‘triggers’), are linked to a set of humanitarian measures (‘early actions’). These are initiated once a trigger is activated and ideally backed up by a pre-agreed financing mechanism, making sure that funding for ‘early actions’ is released in a rapid and reliable way. Despite increasing efforts to extend anticipatory action to other contexts, to date the approach has mainly been applied in relation to hydrometeorological hazards, such as floods, droughts or heatwaves, and overall generated positive effects in addressing the humanitarian impacts of these hazards.

No wonder, then, that the approach is rapidly expanding: According to a recent report compiled by the Anticipation Hub, there were 70 active anticipatory action frameworks in place in 35 countries and another 97 frameworks were under development in 2022. Similarly, multiple large donors, such as the German Federal Foreign Office, have announced or reaffirmed their commitment to anticipatory action. However, three quarters of the 70 active anticipatory action frameworks were implemented either by UN agencies or by actors from the Red Cross Red Crescent movement – the very same actors that piloted and championed the approach throughout the last decade.

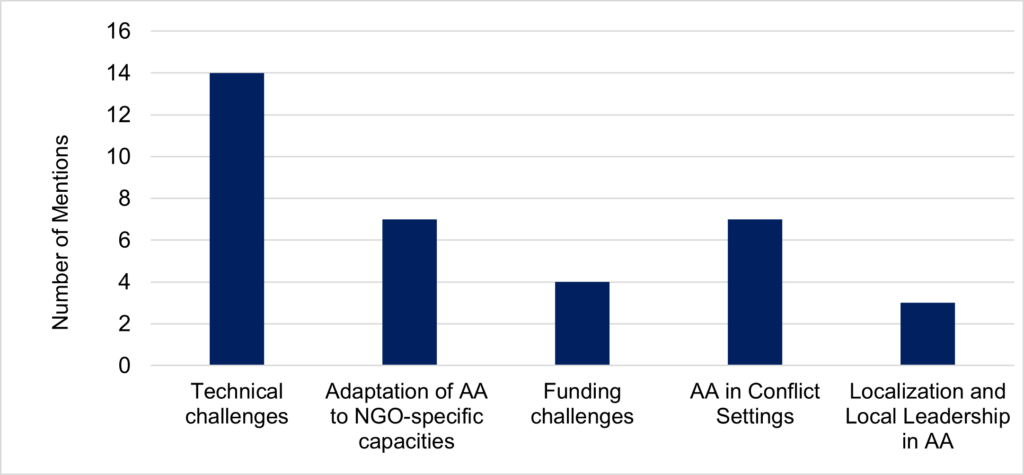

While these figures illustrate the impressive expansion of anticipatory action around the globe, they also allude to the challenges associated with mainstreaming anticipatory action across all levels of the humanitarian ecosystem and making the approach feasible for a broad majority of NGOs – both national and local organisations as well as INGOs based in the Global North. Especially for smaller and medium-sized NGOs, these challenges concern, among others, access to reliable funding mechanisms for anticipatory action, the implementation of anticipatory action in conflict settings or the technical expertise required to develop reliable trigger models (Figure 1). The following sections will focus on the issue of trigger development and underline the importance of more flexible approaches to anticipatory action in general and trigger development in particular, highlighting the role that local expertise and partnerships can play in this context.

Towards more flexible approaches to anticipatory action and trigger development

The technical challenges associated with identifying, accessing and analysing appropriate forecast data to build reliable trigger models are among the most frequently cited barriers for NGOs seeking to implement anticipatory projects. Consequently, many NGOs are moving towards more flexible approaches to anticipatory action in general and trigger development in particular, for example in the form of hybrid trigger models. These flexible approaches often rest on a combination between the monitoring of (quantitative) forecast data and (qualitative) assessments to determine when a trigger is activated and early actions should be implemented. For example, organisations like FAO or the START network have enhanced flexibility and context-specificity by integrating both ‘hard’ indicators, such as declining crop yields or rainfall levels to flag an imminent drought, and ‘soft elements’, such as reviews of the available data and situation on the ground by local expert panels, into single predefined decision-making frameworks for early action. While the accuracy and effectiveness of these models still depend on thorough knowledge of the respective context as well as impact of past disasters, they have emerged as a solid middle ground between entirely decision-based (soft) triggers, which have also been used by some organisations in the past, and purely data-driven initiatives, and thus can reduce the required time and resources vis-à-vis traditional approaches to trigger development.

Traditionally – for example, within the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement – trigger development follows and well-defined but sometimes lengthy process, that highly relies on quantitative data and automated procedures, combining climate- and weather-related forecasts with an impact analysis of past events and involving a variety of stakeholders – from (other) humanitarian actors to meteorological experts. Due to their demonstrated effects to reduce human suffering, these triggers still serve as a benchmark within the discourse on trigger development for anticipatory action. At the same time, this traditional process of trigger development rests on crucial assumptions that are not always met: On the one hand, the availability of (quantitative) data and the infrastructure to produce reliable and context-specific forecasts may be limited in certain settings, particularly in conflict contexts. On the other, the necessary resources to replicate this process, including time, technical expertise, networks or funds, might not always be available, especially to smaller and medium-sized NGOs.

Hence, flexible approaches, such as hybrid trigger models, are increasingly considered by many humanitarian organisations, because they lower the threshold to engage in anticipatory action without moving away from its constitutive elements, like triggers and early actions. Save the Children, for example, has recently launched its Framework for Anticipatory Action, in which it distinguishes between full-fledged AA projects and a “light touch approach” to anticipatory action for contexts, in which some of the abovementioned preconditions are not met. The “light touch approach” still includes thorough monitoring of predetermined hazard variables and predefined action plans, though the trigger itself might rest on decisions by local experts or experience from past events. Ideally, approaches like the one adopted by Save the Children allow NGOs to gradually move towards more anticipatory ways of working rather than taking the decision between ‘doing a full-fledged AA project’ and ‘doing no AA at all’.

Bringing local knowledge in and taking localisation seriously

One way of putting this flexible understanding of trigger development into practice and to develop basic trigger models is by building on local knowledge and expertise: Communities and local organisations in areas at risk to certain hazards, such as floods or tropical storms, often have a very comprehensive understanding of risks and vulnerabilities, including the crucial question for humanitarian actors at which point a disaster will exceed local coping capacities. Previous research has highlighted the potential of integrating this knowledge into early warning systems and disaster risk management (DRR) more broadly. Similarly, local communities might have identified own early warning signs to assess hazard risks. Though not an entirely new idea to the broader DRR discourse, it remains underexplored, how these local practices can be leveraged more systematically for anticipatory action frameworks and the specific process of trigger development.

Especially for smaller and medium-sized Global North-based NGOs that closely work with local partners anyway, local knowledge, risk perceptions and practices can be an entry point for trigger development that they can build upon, support, quantify (if desired), and triangulate with other information or forecasts. In the Asia Pacific region, for example, some organisations are currently experimenting with two-step triggers – a well-established approach anyway (for common examples, consult the Anticipation Hub’s trigger database) – that systematically combine local knowledge and scientific evidence to address flood risks: A pre-activation trigger rests on a community-based early warning system between upstream and downstream communities that takes locally established and monitored early warning signs into account, such as changes in the color or sound of a river stream or the amount of sand and debris in the water. In a second step, this early warning can then quickly be triangulated with complementary data, for example from the Global Flood Awareness System (GloFAS), to determine whether the situation is likely to improve or deteriorate and whether the implementation of predetermined early actions can be justified. Although respective projects are still in a pilot phase and rigorous monitoring and evaluation is needed to further test and refine these models, generally moving towards a more systematic integration of local knowledge and expertise can be a promising pathway to facilitate flexible trigger development and scale up anticipatory action, including its extension to hazards like locust plagues that are just beginning to be explored for anticipatory action frameworks.

Building on local knowledge and partnerships with local actors more systematically, however, is not a self-fulfilling prophecy, but requires a general shift towards locally-led anticipatory action. On the one hand, the existing funding mechanisms for anticipatory action are not yet widely accessible for local actors: While multilateral funding structures are often limited to designated actors, in few contexts only have anticipatory approaches been explicitly and successfully integrated into local or national funding plans. On the other hand, sustainably strengthening the capacities of national and local NGOs is crucial to create the operational foundations to act early, including the building of technical expertise and logistical flexibility as well as a solid understanding of key components and mechanisms of anticipatory action. Recent initiatives seek to address these gaps: A joint capacity strengthening project by the IFHV and VENRO targets German NGOs and their local partners and includes a strong component on Anticipatory Action. Likewise, the Welthungerhilfe’s Anticipatory Humanitarian Action Facility (WAHAFA) supports and funds the development and implementation of anticipatory action frameworks at the local level. However, these initiatives are not a substitute for the creation of more inclusive funding structures and the widespread allocation of funds to boost local capacities and can thus only be the starting point of a systemwide shift towards locally-led anticipatory action.

Conclusion and Outlook

Evidence suggests that trigger development is one of the main barriers for NGO engagement in Anticipatory Action. A more nuanced and flexible understanding of anticipatory action in general and trigger development in particular that combines local knowledge and scientific information would not only lower this (technical) barrier to engage in AA, but also make it easier especially for smaller and medium-sized NGOs to kickstart anticipatory action within their organisation and networks. Although the discourse on the value of local knowledge is not new to the broader field of disaster risk reduction, it has not yet been explored how it can be systematically built upon in the concrete field of trigger development for anticipatory action. In addition to the initiatives mentioned above, a designated research component within the joint project of IFHV and VENRO will therefore collect further evidence and best practices on the integration of local knowledge and partnerships into trigger development to support this process. However, to build upon the full potential of local knowledge and actors for trigger development and anticipatory action more broadly, more structural and systemic changes are necessary.

Sören Schneider s a research associate at the Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (IFHV) of the Ruhr-University Bochum, where he coordinates a humanitarian training program on anticipatory humanitarian action and supports the publication of the annual WorldRiskReport. He also leads a research component on localised trigger development in anticipatory action and has further experience in publication, research and teaching on anticipatory action.

Related posts

Climate Change and Humanitarian Change

Is it right to prioritise fragile states in the climate crisis?

31.05.2023At a turning point - climate change and the responsibilities of humanitarian actors

17.10.2022