Toward an Understanding of Zika's Neurological Dangers

New research comes closer to connecting the virus with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré.

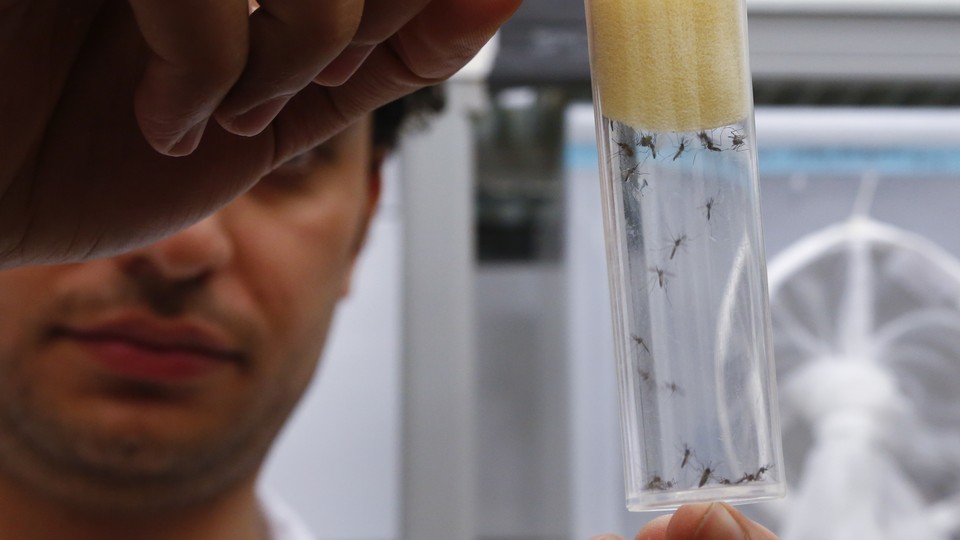

The ubiquitous caveat in stories about the Zika virus thus far: Despite the huge uptick of cases in the birth defect microcephaly in Brazil, and despite the verrrrry suspicious correlation of this uptick with the arrival of Zika in the country, we don’t know for certain that Zika causes microcephaly. The same goes for the neurological disorder Guillain-Barré, cases of which have also climbed in time with the Zika outbreak.

“More research is needed,” scientists and government officials have chorused, declaring a quest to get good science on the virus as quickly as possible. And it’s starting to show results.

A new study published Friday in Cell Stem Cell shows how Zika affects neural stem cells, which appear to be particularly vulnerable to the virus. This may be the mechanism by which Zika could cause microcephaly, a condition in which a baby is born with an unusually small head due to incomplete brain development.

Researchers examined the effects of a strain of Zika virus (not the same strain currently circulating in the Americas, but the original strain, from Africa) on three different kinds of cells: induced pluripotent stem cells (stem cells with the potential to turn into any kind of cell in the body); human cortical neural progenitor cells, or NPCs (stem cells that are destined to become brain cells, specifically); and immature cortical neurons (young brain cells).

They found that the Zika virus absolutely loves cortical neural progenitor cells. It just loves ‘em. Even with a relatively small viral load (one virus for every 10 cells), after three days, 65 to 90 percent of the brain stem cells were infected, meaning the cells were reproducing the virus.

“These NPCs after infection, they become a viral factory,” says Guo-Li Ming, a professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University and one of the study’s authors. In contrast, the infection rate in the pluripotent stem cells and the immature neural cells was pretty low—under 20 percent for each.

As they’re making all these viruses, the NPCs’ growth and reproduction cycle is slowing down, and the cells are dying. Because a fetus’s nervous system is mostly developed by the second trimester, this research suggests that fetuses would be most at risk during the first trimester, when NPCs abound. Research has already shown that Zika can cross the placenta—the virus was found in the amniotic fluid of two Brazilian pregnant women whose fetuses were diagnosed with microcephaly. Once it does cross that barrier, it may target these brain stem cells, which could be what’s causing the condition.

This week also saw research advancing the connection between Zika and Guillain-Barré: A study published in The Lancet on Monday offered the first real evidence that Zika can cause Guillain-Barré syndrome—an autoimmune disease in which the immune system targets a person’s nervous system. Guillain-Barré can completely paralyze people, to the point where they can’t breathe. Most people recover, though they may not fully regain their strength, according to the National Institutes of Health.

The Lancet study looked at 42 patients who were diagnosed with Guillain-Barré at a Tahiti hospital during the 2013-2014 Zika outbreak in French Polynesia. Ninety-three percent of the Guillain-Barré patients had anti-Zika antibodies in their blood, and 88 percent of them reported that they’d had other Zika-esque symptoms within six days of the onset of their neurological symptoms.

With microcephaly, the causal connection is still not there. But thanks to this new study, we’re getting closer to establishing it. With the outbreak now affecting 29 countries in the Americas and two U.S. territories (the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, scientists are responding to the emergency by conducting research at a much faster pace than usual.

The researchers on the microcephaly study—who hail from Johns Hopkins, Florida State University, and Emory University—turned it around in about a month. “Usually this will take at least six months to a year to do from a single lab,” Ming says. “It’s really teamwork.”

Thanks to this kind of quick work, it’s getting clearer and clearer that we should be thinking about Zika as a neurological threat, first and foremost.

As far as its bodily symptoms go, Zika is “a simple, like a cold kind of virus,” Ming says. “I guess it's probably not that bad.” And four out of five people infected with Zika will not come down with the the characteristic fever, headaches, and joint pain.

“[But] actually it looks like there’s more and more studies indicating its connection to neurological disorders,” Ming says. “I think this is a very very unique case, because Zika virus is one type of flavivirus, and there's several other viruses in this family such as yellow fever and West Nile. But apparently there is no connection between those viruses and microcephaly, so Zika virus is doing something unique.”

Of course, more research, as ever, as always, is needed.